Established genetic studies showed that no such link has been found in other Southeast Asian groups.

Human Biology Genetic study reveals some Aetas and Indians share ancient ancestry

Complete mtDNA genomes of Filipinos reveal recent and ancient lineages

11WednesdaySep 2013

Posted by Nath in Origin of the Filipino, Science News from the Islands

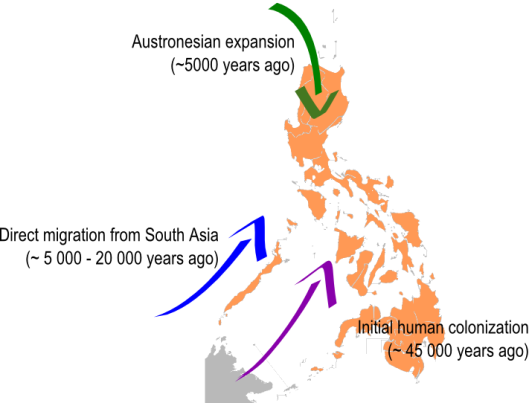

Three migrations were seen upon analysis of mtDNA genomes of 14 ethnolinguistic groups.

The plot thickens!

It still fascinates me how regions of the earth have been reached and populated by humans. Particularly, I am curious how humans ‘conquered’ the islands of the Philippines. Curious because it says where I, a Filipino, and the rest of Filipinos came from.

I’ve written two blog posts about this topic already (here and here). Let me first summarize what I think are notable points in these studies. The first post is about the diversity of mtDNA in the Philippines by K. A. Tabbada et al [1]. In that paper, they said that the Philippines was populated mostly via Austronesian expansion (~5 000 years ago) but they found out that there is also an ancient lineage that links the Filipinos to people in Near Oceania and Australia (whose founder age they estimate to be ~47 000 years ago). They point out that “there is evidence of substructuring within the lineages which means there is a pattern of long-term in situ evolution.”

The second post I wrote is about the human Y chromosome (NRY) diversity in the islands [2]. In that study, the authors obtained results similar to the mtDNA analysis such as the Austronesian expansion and a founder lineage. Moreover, they were able to connect different Filipino ethnolinguistic groups to different groups outside of the Philippines. Three things are clear in that study: 1) there is genetic diversity even within Philippine populations (even within negrito groups), 2) there is no simple distinction between negrito and non-negrito groups, and 3) there are recent and ancient connections to the people of neighboring countries including Near Oceania and Australia.

Now, a recent paper in the European Journal of Human Genetics studied complete mtDNA of 14 ethnolinguistic groups in the Philippines [3]. They have found out that different groups posses different genetic make-up and that these different genetic make up is caused by different waves of migration that are both recent and ancient and an in situ diversification. These conclusions are similar to the first two papers but what I find striking are the reporting of a direct Indian migration to the islands and the suggestion that every ethnolinguistic group has unique genetic history.

The Indian-Philippine link is noteworthy. The presence of these haplogroups that connect the Filipinos and Indians have NOT been observed in other Southeast Asian groups. AetaZ and Agta groups which posses these haplogroups, “seem to demonstrate a direct mtDNA link between India and the Philippines.” How did the people from South Asia travel to the Philippines without passing through the rest of Southeast Asia? Maybe other regions in Southeast Asia are undersampled?

Another reason why it is remarkable is that it says that the timing of this migration to the islands is in between the initial colonization and the Austronesian expansion. The timing of migration also coincides with a similar migration of South Asians to Australia [4].

There is more to look forward to. The authors said, “although the NRY and mtDNA landscapes of the Filipino population are now described, these genetic systems are just two loci and specifically reflect respectively, male and female genetic histories. A more comprehensive view of Filipino diversity and history can still be sought through genome-wide variation.”

I will be waiting for your results eagerly!

Reference:

[1] K. Tabbada, J. Trejaut, J. Loo, Y. Chen, M. Lin, M. Mirazon-Lahr, T. Kivisild, and M. C. De Ungria, Philippine Mitochondrial DNA Diversity: A Populated Viaduct between Taiwan and Indonesia? Mol. Biol. Evol. 27(1):21–31 (2010). DOI: 10.1093/molbev/msp215

[2] Delfin F, Salvador JM, Calacal GC, Perdigon HB, Tabbada KA, Villamor LP, Halos SC, Gunnarsdóttir E, Myles S, Hughes DA, Xu S, Jin L, Lao O, Kayser M, Hurles ME, Stoneking M, & De Ungria MC (2010). The Y-chromosome landscape of the Philippines: extensive heterogeneity and varying genetic affinities of Negrito and non-Negrito groups. European journal of human genetics : EJHG PMID: 20877414

[3] Delfin F, Min-Shan Ko A, Li M, Gunnarsdóttir ED, Tabbada KA, Salvador JM, Calacal GC, Sagum MS, Datar FA, Padilla SG, De Ungria MC, & Stoneking M (2013). Complete mtDNA genomes of Filipino ethnolinguistic groups: a melting pot of recent and ancient lineages in the Asia-Pacific region. European journal of

The Indian-Philippine link is noteworthy. The presence of these haplogroups that connect the Filipinos and Indians have NOT been observed in other Southeast Asian groups. AetaZ and Agta groups which posses these haplogroups, “seem to demonstrate a direct mtDNA link between India and the Philippines.”

This means we can eat curry now 😋

🤬#Fight Chinese Oppression #Viet Lives Matter 🤠 #Stop Chinese absorption of Vietnam. #Free Uyghurs #Free Austronesians in Taiwan. #free the Tibetans.

Genetic Evidence for Recent Population Mixture in India (nih.gov)

Abstract

Most Indian groups descend from a mixture of two genetically divergent populations: Ancestral North Indians (ANI) related to Central Asians, Middle Easterners, Caucasians, and Europeans; and Ancestral South Indians (ASI) not closely related to groups outside the subcontinent. The date of mixture is unknown but has implications for understanding Indian history. We report genome-wide data from 73 groups from the Indian subcontinent and analyze linkage disequilibrium to estimate ANI-ASI mixture dates ranging from about 1,900 to 4,200 years ago. In a subset of groups, 100% of the mixture is consistent with having occurred during this period. These results show that India experienced a demographic transformation several thousand years ago, from a region in which major population mixture was common to one in which mixture even between closely related groups became rare because of a shift to endogamy.

Introduction

Genetic evidence indicates that most of the ethno-linguistic groups in India descend from a mixture of two divergent ancestral populations: Ancestral North Indians (ANI) related to West Eurasians (people of Central Asia, the Middle East, the Caucasus, and Europe) and Ancestral South Indians (ASI) related (distantly) to indigenous Andaman Islanders.1 The evidence for mixture was initially documented based on analysis of Y chromosomes2 and mitochondrial DNA3–5 and then confirmed and extended through whole-genome studies.6–8

Archaeological and linguistic studies provide support for the genetic findings of a mixture of at least two very distinct populations in the history of the Indian subcontinent. The earliest archaeological evidence for agriculture in the region dates to 8,000–9,000 years before present (BP) (Mehrgarh in present-day Pakistan) and involved wheat and barley derived from crops originally domesticated in West Asia.9,10 The earliest evidence for agriculture in the south dates to much later, around 4,600 years BP, and has no clear affinities to West Eurasian agriculture (it was dominated by native pulses such as mungbean and horsegram, as well as indigenous millets11). Linguistic analyses also support a history of contacts between divergent populations in India, including at least one with West Eurasian affinities. Indo-European languages including Sanskrit and Hindi (primarily spoken in northern India) are part of a larger language family that includes the great majority of European languages. In contrast, Dravidian languages including Tamil and Telugu (primarily spoken in southern India) are not closely related to languages outside of South Asia. Evidence for long-term contact between speakers of these two language groups in India is evident from the fact that there are Dravidian loan words (borrowed vocabulary) in the earliest Hindu text (the Rig Veda, written in archaic Sanskrit) that are not found in Indo-European languages outside the Indian subcontinent.12,13

Although genetic studies and other lines of evidence are consistent in pointing to mixture of distinct groups in Indian history, the dates are unknown. Three different hypotheses (which are not mutually exclusive) seem most plausible for migrations that could have brought together people of ANI and ASI ancestry in India. The first hypothesis is that the current geographic distribution of people with West Eurasian genetic affinities is due to migrations that occurred prior to the development of agriculture. Evidence for this comes from mitochondrial DNA studies, which have shown that the mitochondrial haplogroups (hg U2, U7, and W) that are most closely shared between Indians and West Eurasians diverged about 30,000–40,000 years BP.3,14 The second is that Western Asian peoples migrated to India along with the spread of agriculture; such mass movements are plausible because they are known to have occurred in Europe as has been directly documented by ancient DNA.15,16 Any such agriculture-related migrations would probably have begun at least 8,000–9,000 years BP (based on the dates for Mehrgarh) and may have continued into the period of the Indus civilization that began around 4,600 years BP and depended upon West Asian crops.17 The third possibility is that West Eurasian genetic affinities in India owe their origins to migrations from Western or Central Asia from 3,000 to 4,000 years BP, a time during which it is likely that Indo-European languages began to be spoken in the subcontinent. A difficulty with this theory, however, is that by this time India was a densely populated region with widespread agriculture, so the number of migrants of West Eurasian ancestry must have been extraordinarily large to explain the fact that today about half the ancestry in India derives from the ANI.18,19 It is also important to recognize that a date of mixture is very different from the date of a migration; in particular, mixture always postdates migration. Nevertheless, a genetic date for the mixture would place a minimum on the date of migration and identify periods of important demographic change in India.

-

First People to Settle Polynesia Came from the Philippines

2 years ago

-

Philippines population control and management policies

3 years ago

-

CONSTITUTION OF THE PHILIPPINES

3 years ago

-

The origins of the Filipino Flag

4 years ago

-

Philippines Spanish heritage sites destroyed during WW2

4 years ago