The Kingdom of Ghana

The region lies just south of the Sahara Desert and is mostly savanna grasslands.

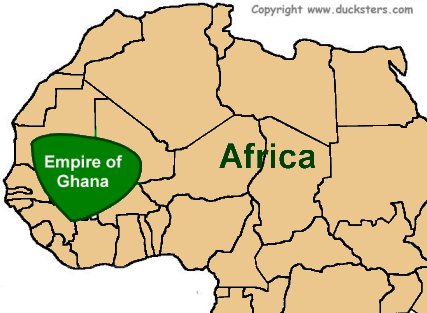

The first outsider to mention Ghana, the kingdom of the Soninke tribe, was an Arab geographer named al-Fazari, writing in the court records of Baghdad in 773. However, the name is confusing for more than one reason. First, the natives called it Wagadu.(9) The king's title was Ghana, and people gradually switched from calling this place "the kingdom of the Ghana" to simply Ghana, much like how the name of a South American king, the Inca, eventually became the name of his people. Second, the kingdom was located on the north bank of the Senegal and Niger Rivers, in what is now southeast Mauritania and southwest Mali, approximately five hundred miles northwest of the modern nation of Ghana.

Read more at: http://www.ducksters.com/history/afr...ient_ghana.php

This text is Copyright © Ducksters. Do not use without permission.

Important archaeological discoveries late in the 1970's have revealed a more complex and much earlier development, well before Ancient Ghana of 300 AD, of early state-like communities and even early cities. Surveys and excavations in this 'Middle Niger' region completed in 1984 at no fewer than forty-three sites of ancient settlement, proved that they belonged to an Iron Age culture developing there since about 250 BC, that the settlements grew into urban centres of natural size and duration'.

Ancient Ghana ruled from around 300 to 1100 CE. The empire first formed when a number of tribes of the Soninke peoples ( who excelled in the use and manufacture of iron had the advantage of superior weapons) were united under their first king, Dinga Cisse. The government of the empire was a feudal government with local kings who paid tribute to the high king, but ruled their lands as they saw fit. Historians say that the use of the horse and camel, along with iron, were important factors in how rulers were able to incorporate small farmers and herders into their empires.

The main source of wealth for the Empire of Ghana was the mining of iron and gold. . The peoples of West Africa had independently developed their own gold mining techniques and began trading with people of other regions of Africa and later Europe as well. Iron was used to produce strong weapons and tools that made the empire strong. Gold was used to trade with other nations for needed resources like livestock, tools, and cloth. They established trade relations with the Muslims of Northern Africa and the Middle East. Long caravans of camels were used to transport goods across the Sahara Desert.

At its heart was Kumbi-Salah which acted as a hive of extensive trade and attracted caravans from a variety of regions. Famed for its gold from the Wangara region, commented upon by the Arab writer Ibn Fazari who called Ghana the land of gold, compered it in size to its northern contemporary Morocco, while salt came to the city from the Sahara. Due to their expertise with iron and other metals, ancient Ghana traded in some of the finest artefacts in the area. Along side cotton, it was also known for its leather work called 'Moroccan Leather' despite the fact that it indeed originated in Ghana.

More wonders came from these African lands as attested too by another Arab geographer Ibn Haukal who commented in amazement on the lucrative trade that flourished in the region. His comments made in 951 CE mentions a cheque produced for the sum of 42,900 golden dinars written for a merchant in the state of Audoghast from a partner in Sidjilmassa in the north! Tales abound of one particular gold nugget weighing 30 pounds! This was truly a land of astonishing wonders and lavished wealth. A far cry from the misconception of the African languishing in barbarity and ignorance!

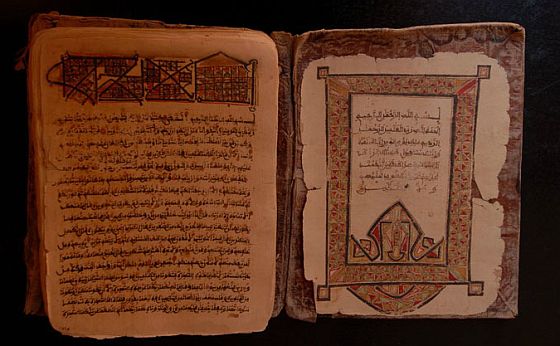

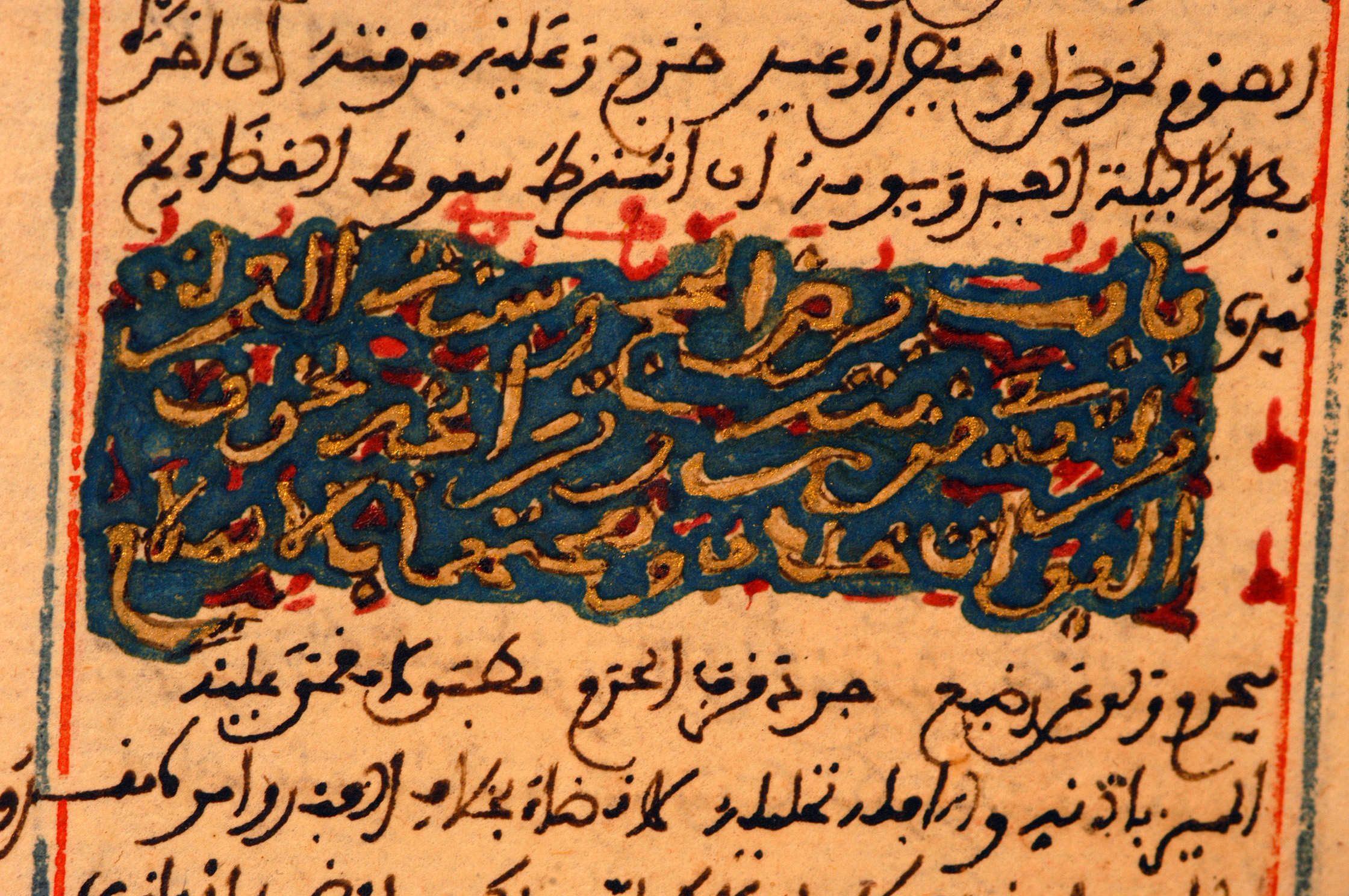

Ibn Khaldun again makes mention of the lifestyle of the ancient Ghanaians while quoting from a book written in 1067 by Abu Ubaid Al-Bakri. He describes the Muslim quarter which had sprung up to facilitate the trans-Saharan trade with north Africa, containing 12 mosques, buildings of stone and acacia wood, schools and centres of education. It was described further as 'the resort of the learned, of the rich and pious of all nations'.

In 990 CE Audoghast to the north was captured and included into the sprawling Ghanaian Empire. It was a fine addition and boasted a dense population including many from as far away as Spain. Its streets were lined with elegant houses, public buildings and mosques. The surroundings were rich in pastoral lands including sheep and cattle, making meat plentiful. Wheat was found in the market places in abundance imported from the north, honey from the south and a variety of foodstuffs from other regions. Robes of blue and red from Morocco was a popular fashion at the time. All which exchanged hands with payments of gold dust, cowrie shells or salt.

Around 1050 CE, the Empire of Ghana began to come under pressure from the Muslims to the north to convert to Islam. The Kings of Ghana refused and soon came under constant attacks from Northern Africa. At the same time, a group of people called the Susu broke free of Ghana. Over the next few hundred years, Ghana weakened until it eventually became part of the Mali Empire.

Around 1054, the Almoravid rulers came south to conquer the Kingdom of Ghana and convert the people to Islam. The authority of the king eventually diminished, which opened the way for the Kingdom of Mali to begin to gain power. The trade that had begun, however, continued to prosper.

Two important sources that have told historians about the history of the Kingdom of Ghana are the writings of a Spanish Muslim named Al-Bakri and archaeological finds. Archaeologists have worked at excavating a site that many believe to be one of the king's cities of the Kingdom of Ghana, Kumbi Saleh.

Historians used to believe that the Arabs brought civilization to Ghana and the rest of West Africa, but recent discoveries like Jenné-Jeno now tell us that the Arabs merely finished the job, by introducing Islam and the Arabic alphabet. The political evolution, from tribe to city-state to confederation to centralized kingdom, most likely took place in the fifth or sixth century, quite some time before the first trans-Saharan contact.

sources: http://xenohistorian.faithweb.com/africa/af05.html

http://www.africankingdoms.com/

.JPG)