By: Rene Bascos Sarabia Jr.

Often when I encounter Foreigners or when I talk to Filipinos, there is often a blanket statement that, ―Filipinos are losers‖, ―We have been defeated and raped by many invaders‖, or that ―Philippine Military History can be seen as a sorry state of constant defeats‖. Quite frankly, this has often created a sense of shame among Filipinos and derision among foreigners who label Filipinos as losers and as the Philippines as the ―Doormat of the region‖. However, to this, I would like to echo the previous quote that once one knows one‘s self and one‘s enemy, then you have nothing to fear. Unfortunately, we barely know ourselves and how much more, the legacy of bravery and valour of our men in uniform? I would like to repair the notion that we were losers and help restore some dignity to Philippine Military History. Hopefully, this article may accomplish that by highlighting key moments in history wherein Filipinos proved particularly valorous.

THE PRECOLONIAL ERA

According to Philippine School text-books (That are so out-dated they still teach the Migration Wave-Theory by Otley Bayer long rendered moot for decades), we were a bunch of tribes with hardly or no mention of a sovereign state. However a cursory review of the modern academic material concerning pre-colonial Philippine History show the opposite,[1] that there were sovereign states that even went toe-to-toe with large Empires and were formidable militaries by their own right. In the next paragraphs, I will outline some cases.

Visayans Raiding China

According to a Chinese chronicler in 1273 named Zhao Rukuo, during the Song Dynasty, a group of raiders pillaged cities in Southern Coastal China which he labelled as ―Pi-sho-ye‖ which supposedly came from southern Taiwan.[2] Later in In A.D. 1273, Ma Tuan Lin also wrote of the same raiders once again pillaging the southern cities of China and he remarked that this Pi-sho-ye had looked different from and had spoken another language as compared to the native inhabitants of Taiwan. Modern scholars such as Isorena of the University of San Carlos postulated that the raiders of Southern China where originally from the Philippines. This is corroborated by the fact that among Visayans, there are several traditions and historical accounts which narrate of how they continuously raided China, the Jesuit Historian Alcina in particular, chronicles how in ages past, people from Dapitan at Bohol had ancestral heroes like Datu Sumanga who established the Kedatuan or Kingdom of Dapitan upon his marriage to the Boholano Princess Bugbung Hamusanum and established Dapitan.[3]

Pangasinan Rivalled the Mongol Empire

Urduja was a legendary Warrior-Princess whos Kingdom‘s location was calculated by Jose Rizal himself to be in Pangasinan, Philippines. In 1916, Austin Craig, an American historian of the University of the Philippines, in "The Particulars of the Philippines Pre-Spanish Past", traced the land of Tawalisi and Princess Urduja to Pangasinan. According, to Arab explorer Ibn Battuta, Princess Urduja led a nation that was a rival to the Mongol Empire and even planned expeditions to India.[4] Recent boats unearthed in Butuan called the Balanghay Boats which are the oldest in Southeast Asia were large enough and useful for medieval point to the fact that Philippine states like Pangasinan surely had the capacity to wage war even against Mongols. Further support of the theory that Pangasinan rivalled the Mongol Empire, was the recently discovered Platinum Ding unearthed near Pangasinan.[5] Since a Ding was an exclusive symbol of Imperial Authority, it is further proof that Pangasinan was of considerable importance, even of Imperial stature.

Wars by Sulu and Manila against Majapahit

During 1365, Majapahit under Maharajah Hayam Wuruk[6] had then invaded the Philippine port principalities of Sulu and Manila which they labelled in the manuscript called Nagarakretagama, as ―Solot‖ and ―Saludong‖. However, sources from China report that Manila and Sulu eventually overthrew Majapahit dominion and Sulu at least had invaded and sacked the then Majapahit province of Brunei before they were driven off by a fleet from the capital, however the people from Majapahit were unable to reclaim the rebel provinces.[7] They were considered so formidable, the Chinese when they came to Sulu (before Islamization) considered the state as equal to Majapahit since one of their rulers was also referred to as a Maharajah.[8]

The Battle of Mactan

The Battle of Mactan is one of the few David vs Goliath moments in Philippine history wherein the smaller and less technologically advanced force of Datu Lapu-Lapu was able to defeat the larger combined forces of Rajah Humabon and the Ferdinand Magellan expedition.[9]

Filipinos as mercenaries in the region and heads of foreign armies

However, there is a little known facet of Philippine military history in the Precolonial era that I would like to point out, in that, due to the war-prone nature of the Philippines during precolonial times, we have proven ourselves to be competent warriors and there were already several overseas trading and mercenary communities of Filipinos all across Southeast Asia and even the Indian Ocean. For example, the people of Luzon (Then called Lucoes) were employed as warriors by the Burmese King as well as the Siamese king during the Burmese-Siamese war of 1547, Lucoes warriors even fought against the Burmese elephant army in a successful defence of the Siamese army of Ayuthaya. The Lucoes were even esteemed in the Sultanate of Malacca, which guards the world‘s busiest maritime chokepoint, the Strait of Malacca. The former Sultan of Malacca decided to retake his city from the Portuguese with a fleet of ships from Luzon.[10] Fernao Mendes Pinto noted that several Filipinos were with the Muslim forces which went to war with the Portuguese in the Philippines. One Filipino by the name of Sapetu Diraja, was the assigned with fortifying Northeast Sumatra (Aru). Pinto also records that another Lucoes was the one who headed the Malays that were in the Moluccas islands.[11] Antonio Pigafetta notes that one Filipino became the chief admiral of the Brunei navy[12] which the historian William Henry Scott says that it is no one but the former Rajah of Manila, Rajah Matanda, otherwise known as Rajah Aceh. One Lucoes named Regimo de Raja even became a Temenggung, the Sea Lord and head of state affairs and security in Portuguese controlled Malacca and he directed the traffic and commerce between the Indian Ocean, the Strait of Malacca, the South China Sea and the Port Principalities of the Philippines.[13]

THE COLONIAL TIMES

One may say that Filipinos were weak in that we were conquered by the Spaniards, but one must know the circumstances as to why, and when one figures it out, one may realize that we weren’t as weak as it may seem. Take the case of our neighbour Indonesia; which had possessed a population running to 11.839 Million in pre-colonial times yet they were defeated by the Dutch Republic which had a population of a mere 1.5 Million during the 1600s.[14] However, in our case it was more understandable since our total population during the beginning of the Spanish conquest, was 667,612 people according to a Spanish census,[15] whereas the Spanish empire had a far larger population of 29 Million, it is thus understandable that the Philippines, which was sparsely populated and also bitterly divided among several warring kingdoms,[16] would fall to the more populous and united Spanish.[17] Especially when the Spanish played the Filipino kingdoms against each other for rapid conquest. Indonesia had a better position then, but they still fell to the Dutch. However, let me also emphasize the fact that the Spanish wouldn’t have been able to maintain their colony as a Spanish possession had it not been consented to by the native Filipinos to whom, the sustenance, commerce and a huge chunk of the military of the Spanish forces themselves, were radically dependent upon.[18] Nevertheless, we shouldn’t have ill-feeling towards Spanish-Filipinos now since during the revolution they happened to have chosen the Philippines over Spain. Now, I do not support the exploitation of our people but there were several instances during the colonial history of the Philippines wherein we proved our mettle and had prevailed against larger odds while we were still serving under a different flag.

Limahong and the 1574 Battle of Manila

One of the early Battles of Manila and the first to have occurred after Spanish conquest was the 1574 Battle of Manila waged between the Chinese pirate Warlord Limahong and the combined Filipino and Spanish-Mexican inhabitants of newly colonized Manila. At first, the city of Manila was besieged and Limahong’s pirate army (Which caused a ruckus in southern China when they sacked several cities there, earning Limahong the name “Terror of Guangdong) then burned down the house of, and killed Martin de Goiti who was the Master-of-Camp of the Spanish.[19] However the siege was broken after a local Filipino by the name of Don Galo combined arms with the Mexico-born Spanish Conquistador, Juan de Salcedo and their total force of 600 fighting men, 300 Spaniards and Mexicans and 300 Filipinos having valiantly fought off the 6,500 pirates of various nationalities; Chinese, Japanese and Korean as well as their 62 War junks (Pirate Ships) led by Limahong and eventually, they were finished off and defeated in campaigns at Pangasinan.[20]

Battles of La Naval de Manila

The Battles of La Naval de Manila was another case of a lopsided victory. It happened at a time when Manila was just recovering from fresh volcanic eruptions at 1633 and 1640, military strength was sapped by war against Filipino Muslims led by Sultan Kudarat of Mindanao and the uprisings by Chinese-Filipinos in the Sangley Rebellions of 1639 and 1640, and in addition to these, the catastrophic sinking of several Manila Galleon flotillas sent from New Spain (Mexico) also forced the country into dire financial straits and reduced the naval strength of the archipelago as well as prevented the arrival of further reinforcements from Spain, Mexico and Peru.[21] In this backdrop, a Dominican Priest by the name of Fr. Juan de los Angeles reported that the Dutch which were then concentrated in Jakarta and Taiwan had considerable strength and power, possessing at least 150 ship and pataches.[22] Furthermore, the military forces prepared by each side against each other was highly unequal. At most the Spanish side which included a lot of Filipino (Kapampangan) volunteers amounted to only 400 soldiers and sailors while the amount of men in the Dutch side were 800 in just one Squadron and three Squadrons were sent. The amount of ships prepared for the battles were wholly in favour of the Dutch side since they employed 19 ships: (16 regular galleons, 3 fire ships) and 16 launches with 470 guns in total (est.). Meanwhile the Spanish-Filipino side was numerically inferior, employing only 4 ships: (3 Manila galleons & 1 galley) plus 4 brigantines with only 68 guns in total. Yet in a series of 5 Battles set in Lingayen, Pangasinan, Marinduque, Mariveles and Corregidor Island, the Dutch combined forces of 19 ships and 800+ (Multiplied by three) or an estimated 3000 men, were defeated by 3 Ships and 400 men from the Spanish-Filipino side.[23] It was considered a miracle by the Archbishop of Manila but I’m sure Filipino made ingenuity and grit also formed a part in that campaign.

A Colony Constantly Besieged yet Surviving

Events such as the Limahong campaign and the battles of La Naval de Manila and so many other battles not mentioned here, were very common occurrences in the Philippines. If you look at the location of the Philippines it’s at the centre of a literal crescent of countries then rivalling it: Japan, Taiwan, China, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei and Indonesia. Thus, from the northeast, north, northwest, west, southwest, south and southeast, there were constant attacks aimed at the Philippines, with reinforcements from Spain or Latin-America only periodically arriving from the East (The only direction that was the source of support). Yet, despite this situation of being constantly attacked on almost all sides, by Japanese Wokou and Ronin from the northeast, north and northwest Chinese pirates from the west, Dutch corsairs from the Southwest and Muslim slavers from the south and southeast, Spanish-Philippines held fast and was maintained as an island of Hispanicity and Catholicism in a sea of hostiles.[24] This is a great achievement for the native inhabitants and the soldier-colonists and missionaries sent to the Philippines especially considering that they were outnumbered by the enemy. However, there was a side effect to all this, the Philippines’ central location also made it a constant warzone and that, there were debates in Spain whether to abandon the costly Philippine archipelago, but eventually, the Philippines remained Spanish due to the argument that it’s a good launchpad for missionary sorties.[25]

Manilamen As Hired Muscle from America to Asia

Filomeno V. Aguilar Jr. in his paper: “Manilamen and seafaring: engaging the maritime world beyond the Spanish realm”, stated therein that Filipinos who were internationally called Manilamen were active in the navies and armies of the world even after the era of the Manila Galleons.[26] Take the case of the famous Argentinian of French descent, Hypolite Bouchard, who was a privateer for the Argentine army. When he laid siege to Monterey California, his second ship, the Santa Rosa which was captained by the American Peter Corney, had a multi-ethnic crew made up of Americans, Spaniards, Portuguese, Creoles (Mexicans), Manilamen (Filipinos), Malays, and a few Englishmen.[27] Mercene, writer of the Book “Manila Men”, proposes that those Manilamen were recruited in San Blas, an alternative port to Acapulco Mexico where several Filipinos had settled during the Manila-Acapulco Galleon trade era.[28] During the Taiping rebellion, Frederick Townsend Ward had a militia employing foreigners to quell the rebellion for the Qing government, at first he hired American and European adventurers but they proved unruly, while recruiting for better troops, he met his aide-de-camp, Vincente [Vicente?] Macanaya, who was twenty three years old in 1860 and was part of the large Filipino population then living in Shanghai, who “were handy on board ships and more than a little troublesome on land’, as Caleb Carr journalistically put it.[29] Smith, another writer about China also notes in his book: “Mercenaries and Mandarins” that Manilamen were ‘Reputed to be brave and fierce fighters’ and ‘were plentiful in Shanghai and always eager for action’.[30] During the Small Sword Uprising, when secret-society militia gangs mounted a coup and took over Shanghai for seventeen months,[31] Manilamen as well as French, British and Americans were hired as mercenaries by both sides.[32] By July 1860, Ward’s force of Manilamen ranging from one to two hundred mercenaries successfully assaulted Sung-Chiang Prefecture.[33] Ward’s Foreign-Arms Corps had Manilamen, Americans, and Europeans, in it, however, rigid discipline (including capital punishment), caused much desertions but the Manilamen were among the tough few who remained.[34] The Chinese called them Lu¨song Yiyong (foreign militia from Luzon), Manilamen were the major part of Ward’s army even after the recruitment and training of Chinese warriors. These men were placed under the direct control of Macanaya and comprised Ward’s corps of personal body guards until Ward’s death on September 1862.[35] Asides from the roles Filipinos had as valued mercenaries in China and sailors working for Argentina, Filipinos also rushed in and came to the defence of a then newly independent America threatened by a potential British re-annexation during the British-American War of 1812 when General Andrew Jackson noted that “Manilamen” fought under his banner while being led by Jean Baptiste Lafitte in the defence of New Orleans against the British.[36] One Filipino by the name of Augustine Feliciano even continued to serve in the U.S. Navy.[37] Considering that Asia and the Americas are at the opposite sides of the globe and Filipinos still played an active role in the successful revolutions and defence of the nations’ therein, it’s outstanding how this fact is ignored and the military ability of Filipinos are ridiculed.

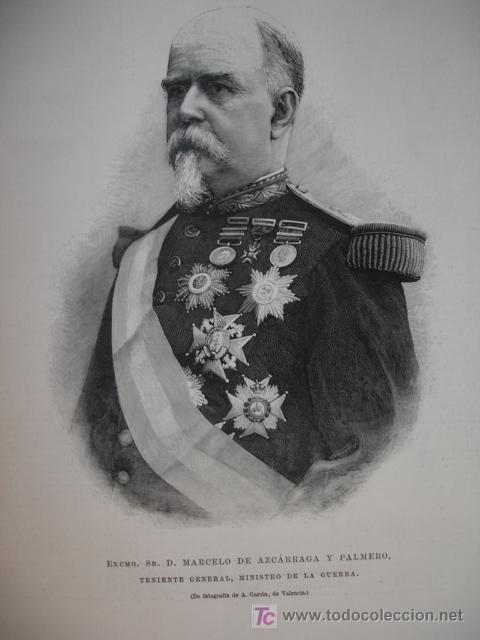

Filipino Generals in Mexico and Spain

Unbeknownst to a lot of Filipinos, during the 1800s, before the onset of the Philippine revolution, Filipinos have repeated their pre-colonial reputation of having talented officers serve as highest or most celebrated heads of armies in other nations, I would like to point out the cases of Generals Isidoro Montes de Oca and Francisco Mongoy of Mexico as well as General Marcelo Azcarraga Palmero of Spain as examples. According to journalist Floro L. Mercene, citing the English teacher from Acapulco, Ricardo Pinzon, there were 200 Filipinos who were recruited for the Mexican revolution in the city of Acapulco and two Mexicans of Filipino descent were Brigade Commanders in Mexico during the Mexican revolution, they were Isidoro Montes de Oca and Francisco Mongoy, [38] at the end of the Mexican war for independence, Isidoro Montes de Oca in particular achieved the rank of Captain-General as he gained fame during a battle where he stood out, which was in the Treasury of Tamo, in Michoacán at September 15, 1818, in which the opposing forces numbered four times greater, yet they were totally destroyed by his forces. [39][40] Then, there is the case of another General of Filipino descent, this time in Spain, General Marcelo Azcarraga Palmero. Azcarraga was a well accomplished soldier, born in Manila and having studied in the University of Santo Tomas, he was sent to Spain and obtained the rank of Captain in three years and became a Major after his services against the O’Donnell revolution which also occurred in Spain. Afterwards he was sent to New Spain (Mexico), Cuba and Santo Domingo. He eventually joined the movement for the Bourbon dynasty’s restoration to the throne of Spain after an anti-monarchist uprising inspired by the French Revolution. He eventually achieved the rank of Lieutenant-General and was awarded two orders of merit, the Cross of San Fernando and the Order of the Golden Fleece, the most prestigious and exclusive Order of Merit in the World, this, after he became Prime Minister of the whole Spanish empire. He was the only Prime Minister of Spain of Filipino descent. This fact is ironic considering how Marcelo Azcaraga Palmero’s ancestors were part of the Palmero Conspiracy aiming for Philippine independence against Spain in the midst of the Latin American wars of independence.[41]

The Courage of the Philippine Revolution and Philippine-American War

The Philippine Revolution which eventually erupted against a decadent Spanish Empire which had degenerated in its rule over the Philippines was accomplished despite several disadvantages to Filipinos, chief among which was the lack of weapons and ammunition as well as the absence of a navy to counter blockades in the archipelago. Often, when the Filipino fought the Spaniards, they resorted to guerrilla tactics, hand-to-hand combat and merely used machetes or swords compared to the more well-armed Spaniards.[42] Yet the poorly armed Filipinos succeeded, but was still magnanimous in victory, as was the case of the Siege of Baler where the Filipinos respected the brave Spanish side and even sent them off back to Spain or offered some of them citizenship in the New Republic. The Philippines was successful in the revolution in that, by the time of the proclamation of the First Philippine Republic on June 12 1898, the First Republic had basically controlled most of the archipelago, except for Manila which was then occupied by the Americans who betrayed their previous promise to support Philippine Independence and instead colonized the Philippines. Yet, even in the face of war-weariness, ruined lands and reduced manpower since they just exhausted themselves in a war against Spain, the Filipino people still fought the Americans in the Philippine-American war even when they knew they would fail. This shows the valiant spirit of Filipinos in that, they were willing to die for a lost cause against larger odds (America was more technology advanced than the Philippines then and had an army and population several times larger than what can be fielded by the First Philippine Republic), yet, even in the face imminent defeat, we didn’t surrender and didn’t back down. Thus, the Americans were taken aback since the casualties they incurred in the Philippine “Insurrection” as what they officially called the war here, to demote its status, actually caused more casualties to Americans than the entirety of the Spanish-American “War”.[43]

The Filipinos and the Japanese Occupation

After the Filipinos came under American rule, the Philippines were soon the target of Japanese Imperialists during World War 2. The attack on the Philippines just happened 10 hours after the initial bombardment at Pearl Harbour.[44] General Douglas MacArthur, who was the son of the former American Governor-General of the Philippines, Arthur MacArthur, and was also a close friend of the former Revolutionary turned President of the Philippine-Commonwealth, Manuel L. Quezon, was caught off-guard by the surprise Japanese attack. Despite the suddenness of the attack, the combined American and Filipino forces managed to delay the Japanese so much that their schedule for the total conquest of the archipelago was set aback by about 3 months and in a time when the Axis powers seemed invincible; with France, Poland, Libya, Egypt, parts of China, Singapore and Malaysia having already fallen while Britain and Australia were threatened by Axis hands, the battling bastards of Bataan led by General Douglas MacArthur where a light in the midst of the dark for the Allied forces[45] since the Philippines was an island of Resistance in the midst of an Axis tsunami because by that time, Taiwan and China to the north were under the Japanese, as well as Vietnam and Thailand to the West; Malaysia and Indonesia to the South and the Marianas, Carolines, and Marshall Islands as well to the east, yet Filipinos and Americans in the Philippines stood strong and resisted despite this complete envelopment by the enemy. This bought precious time for Australia to adequately prepare herself for a Japanese assault.[46][47] Still, in the midst of the Japanese occupation, after the Philippines fell, Filipino and American guerrillas managed to harass the Japanese so much that guerrillas controlled as much as 60% of the total land area in the Philippines, mostly rural zones, mountains and jungles and that, the Japanese only managed to subjugate twelve out of forty eight provinces.[48] By the time of the American liberation of the Philippines, which prodigiously used the intelligence and tactics of the Philippine guerrilla forces, the Filipinos have already proven their worth in battle. However, there was the unfortunate fact that at least 1 Million Filipinos who were mostly civilians died in the war.[49] There was also the irreplaceable loss of many of Manila’s heritage especially Intramuros’ centuries old structures since Manila became the only urban-fighting area in the Pacific Theatre of the War and it was so thoroughly levelled that it was the second most destroyed city in the world during World War 2, after Warsaw, Poland.[50]

CONTRIBUTIONS OF A FREE PHILIPPINES

After the horror of the Second World War was concluded, America finally fulfilled her promise to the war torn Philippines that she be given independence. However, no sooner than when the wounds of conflict were being healed was when the Philippines were once again plunged into wars. This time, among campaigns set abroad.

Expeditions to the Korean War

The Korean War was the last known international-scale conventional war wherein the Philippines have had an active participation and they proved themselves to be courageous, loyal and effective soldiers in the midst of the Korean War. The battles where the Fighting Filipinos distinguished themselves include the Battle of Eerie Hill where a certain Lieutenant Fidel Ramos a graduate of the Philippine Military Academy and eventually West Point at America, comes to the fore before he eventually became the future President of the Philippines.[51] Then there are also the other battles like the Battle of Imjin River and operation Tomahawk.[52] However, the battle the Filipinos are most famous for in the Korean War was the Battle of Yultong Bridge. According to Art Villasanta in his article “Filipino Soldiers’ story of Korean War: Valor redux”, he cited Korean War Veteran Jesus Dizon who was part of that battle, that in the battle, when forces from other nations retreated, the Filipinos in the 10th Battalion Combat Team stood alone and surrounded; and the mere 900 Filipinos fought 40,000 Chinese at peak strength.[53] If the Filipinos weren’t brave enough to have stood their ground against impossible odds and have retreated like the others then the US third infantry wouldn’t have successfully withdrawn and later turned the tide of the war.[54]

Recollection

Now that one understands that the popular view, that we are losers and push-overs militarily, isn’t founded on truth, once one gets acquainted with the tenacious fighting Filipinos have done even in the face of defeat, as well as the several instances where Filipinos won against enormous odds, one should feel pride instead of shame in our military exploits in that we have proven ourselves valiant warriors who were zealous in fighting but also happened to be a nation that never invaded another yet have had an active participation in defending others. When this is compiled with the function of our modern OFWs who also dispersed among all the world, then we can tap our military history and overseas communities abroad in assisting others,[55] and mark that as a symbol of “soft power”. Due to our linkages we can better contribute to the concert of nations and work for the uplifting of man and nature as well as the glorification of God. Even though we still face challenges like modern forms of conflict such as terrorism and cyber-warfare, know that our people have faced worse. Nevertheless, despite our glorious but ignored military history, I caution Filipinos in order to not develop unnecessary pride. I once again quote Sun Tzu: “Appear weak when you are strong, and strong when you are weak.” Thus, we must clothe our glory in a mantle of humility. After all, the Philippines wouldn't be a source of so many brilliant military feats had our people and land had not been exhausted by wars and disasters. And just as muscles are strengthened by weakening them first, such is Gospel truth... 2 Corinthians 12:9 “But He said to me, “My grace is sufficient for you, for My power is perfected in weakness.” Therefore I will boast all the more gladly in my weaknesses, so that the power of Christ may rest on me.”

So the next time somebody demeans your people and your nation, rest assured that you have no need to fear any further battle since you have known your heritage and by extension, yourself.

REFERENCES:

[1] Scott, William Henry (1984). Prehispanic Source Materials for the Study of Philippine History. Quezon City: New Day Publishers.

[2] Jobers Bersales [ https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/421631/raiding-china ]

[3] Athena Garcia, Dapitan Kingdom of Bohol: An Attempt to Investigate The Facts Behind The Legend [ https://www.academia.edu/6171458/Dapitan_Kingdom_of_Bohol ]

[4] Ibn Battuta, pp. 886–7.

[5] "5 Things Why This Artifact May Change World History" By Kasaysayan Hunters. (2018) [

[6] Day, Tony & Reynolds, Craig J. (2000). "Cosmologies, Truth Regimes, and the State in Southeast Asia". Modern Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. 34 (1): 1–55.

[7] History for Brunei Darussalam: Sharing our Past. Curriculum Development Department, Ministry of Education. 2009. p. 44.

[8] Tan, Samuel K. (2010), The Muslim South and Beyond, University of the Philippines Press

[9] Angeles, Jose Amiel. "The Battle of Mactan and the Indigenous Discourse on War." Philippine Studies vol. 55, No. 1 (2007): pp. 3-52.

[10] Barros, Joao de, Decada terciera de Asia de Ioano de Barros dos feitos que os Portugueses fezarao no descubrimiento dos mares e terras de Oriente [1628], Lisbon, 1777, courtesy of William Henry Scott, Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society, Quezon City: Ateneo de Manila University Press, 1994, page 194.

[11] Pinto, Fernao Mendes (1989) [1578]. "The travels of Mendes Pinto". Translated by Rebecca Catz. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

[12] Pigafetta, Antonio (1969) [1524]. "First voyage round the world". Translated by J. A. Robertson. Manila: Filipiniana Book Guild.

[13] Manansala, Paul Kekai “The Philippines and the Sandalwood Trade”

Website: [ http://sambali.blogspot.com/2014/02/the-philippines-and-sandalwood-trade-in.html ]

[14] Two Thousand Years of Economic Statistics, Years 1–2012; Volume 1 (Page 15) By Alexander V. Avakov.

[15] The Unlucky Country: The Republic of the Philippines in the 21St Century By Duncan Alexander McKenzie (Page xii)

[16] Barrows, David (2014). "A History of the Philippines". Guttenburg Free Online E-books. 1: 139. Fourth.—“In considering this Spanish conquest, we must understand that the islands were far more sparsely inhabited than they are to-day. The Bisayan islands, the rich Camarines, the island of Luzon, had, in Legaspi's time, only a small fraction of their present great populations. This population was not only small, but it was also extremely disunited. Not only were the great tribes separated by the differences of language, but, as we have already seen, each tiny community was practically independent, and the power of a dato very limited. There were no great princes, with large forces of fighting retainers whom they could call to arms, such as the Portuguese had encountered among the Malays south in the Moluccas.”

[17] A. Maddison, The World Economy Volume 1: A Millennial Perspective Volume 2, 2007, p. 238

[18] In 1794, Governor Aguilar described in romanticized terms to Viceroy Count of Campo de Alange the frugality of indios and their tolerance of heat, humidity, hurricanes, thunder, and earthquake. CSIC ser. Consultas riel 301 leg.8 (1794).

[19] Bourne, Edward Gaylord (16 June 2004). Blair, Emma Helen; Robertson, James Alexander (eds.). "The Philippine Islands, 1493-1803 — Volume 04 of 55". Gutenberg.org [ http://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/12635/pg12635-images.html ]

[20] Charles A. Truxillo (2012). Crusaders in the Far East: The Moro Wars in the Philippines in the Context of the Ibero-Islamic World War Jain Publishing Company. p. 92

[21] Fayol, Joseph. (1640–1649). A contemporary description of this earthquake is furnished in a rare pamphlet (Manila, 1641), containing a report of this occurrence made by the order of Pedro Arce, bishop of Cebu; part of it is reprinted by Retana in his edition of Zunfiiga's Estadismo, ii, pp. 334–336.

[22] De los Angeles, O.P., Juan. (March 1643)

[23] Cortez, O.P., Regino. (1998). The Story of La Naval. Quezon City: Santo Domingo Church.

[24] THE IMPOSSIBLE COLONY: PIRACY, THE PHILIPPINES, AND SPAIN’S ASIAN EMPIRE by Kristie Patricia Flannery

[25] Dolan, Ronald E. (Ed.). (1991). "Education". Philippines: A Country Study. Washington: GPO for the Library of Congress. [ http://countrystudies.us/philippines/4.htm ]

[26] Filipinos in Mexican history By Floro L. Mercene [ https://archive.is/20121209185353/http://www.ezilon.com/cgi-bin/information/exec/view.cgi#selection-1519.1-1519.20 ]

[27] Delgado de Cantú, Gloria M. (2006). Historia de México. México, D. F.: Pearson Educación.

[28] Mercene, Manila men, p. 52.

[29] Ibid., p. 54

[30] Caleb Carr, The devil soldier: the story of Frederick Townsend Ward, New York: Random House, 1992, p. 91.

[31] González Davíla Amado. Geografía del Estado de Guerrero y síntesis histórica 1959

[32] Smith, Mercenaries and mandarins, p. 29.

[33] Bryna Goodman, Native place, city, and nation: regional networks and identities in Shanghai, 1853–1937, Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1995, pp. 72–83.

[34] Smith, Mercenaries and mandarins, p. 29.

[35] Carr, Devil soldier, p. 107

[36] Ibid., p. 30.

[37] Ibid., p. 85. For an exploration of Manilamen as mercenaries and filibusters in relation to the person and work of Jose´ Rizal, see Filomeno Aguilar Jr, ‘Filibustero, Rizal, and the Manilamen of the nineteenth century’, Philippine Studies, 59, 4, 2011, pp. 429–69.

[38] Williams, Rudi (3 June 2005). "DoD's Personnel Chief Gives Asian-Pacific American History Lesson". American Forces Press Service. U.S. Department of Defense.

[39] Silva, Eliseo Art Arambulo; Peralt, Victorina Alvarez (2012). Filipinos of Greater Philadelphia. Arcadia Publishing. p. 9.

[40] González Davíla Amado. Geografía del Estado de Guerrero y síntesis histórica 1959

[41] Joaquin, Nick (1990). Manila, My Manila. Vera-Reyes, Inc.

[42] A History of The Filipino Revolt (From The Tagalog Perspective) by Tom Matic IV

[ https://www.1898miniaturas.com/en/article/history-filipino-revolt/ ]

[43] “The Encyclopaedia of the Spanish-American and Philippine-American Wars” Edited By: Spencer Tucker.

[44] MacArthur General Staff (1994). "The Japanese Offensive in the Philippines". Report of General MacArthur: The Campaigns of MacArthur in the Pacific Volume I. GEN Harold Keith Johnson, BG Harold Nelson, Douglas MacArthur. United States Army. p. 6.

[45] Most of the Japanese commanders who opposed General MacArthur in the Philippines generally agreed that the withdrawal into Bataan was an excellent strategical maneuver. "The fact that the Americans entered Bataan where there were well-prepared positions was a brilliant move strategically. American resistance was very fierce," said Lt. Gen. Susumu Morioka, Commanding General, 16th Division. While some of the Japanese commanders thought that General MacArthur would move into Bataan, the operation caught the bulk of them unawares, for they did not anticipate that it would be done so soon or so efficiently. The following statements are typical of their reactions: "We were completely surprised by General MacArthur's withdrawal to Bataan. We thought the Americans were cowards at the time. However, later studying the move objectively, I have come to believe that it was a great strategic move," said Colonel Akiyama, Organization and Order of Battle Department, Imperial General Headquarters. "The Japanese had never planned for or expected a withdrawal to Bataan," said Colonel Sato, Fourteenth Army Staff Operations. "It had been anticipated that the decisive battle would be fought in Manila. The Japanese commanders could not adjust to the new situation caused by the withdrawal of General MacArthur's forces into Bataan which they learned about from wireless, intelligence, and aerial reconnaissance around 28 December." Interrogation Files, G-2 Historical Section, GHQ, FEC.

[46] Allied estimates of enemy intentions were accurate. As early as 2 February 1942, Imperial General Headquarters had ordered the South Seas Detachment to prepare for the invasion of Port Moresby in coordination with the Fourth Fleet. Japanese First Demobilization Bureau Report, Southeastern Area Operations Record, Part III, "Operations of the Eighteenth Army," Vol I, pp. 4-6, G-2 Historical Section, GHQ, FEC. The reports of the Japanese First and Second Demobilization Bureaus are operational histories prepared by former Japanese Army and Navy officers, all of whom participated in some phase of the war. The purpose of these reports is to document fully the history of the Japanese Armed Forces in World War II.

[47] ADBC (American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor) Museum. Morgantown Public Library System [ https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/MacArthur%20Reports/MacArthur%20V1/ch01.htm ]

[48] Caraccilo, Dominic J. (2005). Surviving Bataan And Beyond: Colonel Irvin Alexander's Odyssey As A Japanese Prisoner Of War

[49] Rottman, Gordon L. (2002). World War 2 Pacific Island Guide – A Geo-Military Study. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. p. 318

[50] Sionil, Jose F. (2010) Manila, Hiroshima and the Bomb [ https://www.nytimes.com/2010/08/14/opinion/14iht-edjose.html ]

[51] Ben Cal (2019) “FVR recalls Korean War exploits” Publisher: Philippine News Agency [ https://www.pna.gov.ph/articles/1073067 ]

[52] Villahermosa, Gilberto N (2009), Honor and Fidelity: The 65th Infantry in Korea, 1950–1953

[53] Art Villasanta (2012) Published by Philippine Daily Inquirer (“Filipino Soldiers’ story of Korean War: Valor redux”)

[54] Chae, Han Kook; Chung, Suk Kyun; Yang, Yong Cho (2001). "The Korean War" Pages 625 and 627.

[55] See James A. Tyner, ‘Global cities and the circuits of labor: the case of Manila, Philippines’, in Filomeno Aguilar, ed., Filipinos in global migrations: at home in the world?, Quezon City: Philippine Migration Research Network and the Philippine Social Science Council, 2002, pp. 60–85; Helen Sampson, ‘Transnational drifters or hyperspace dwellers: an exploration of the lives of Filipino seafarers aboard and abroad’, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 26, 2, 2003, pp. 253–77; Steven C. McKay, ‘Filipino sea men: constructing masculinities in an ethnic labour niche’, Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 35, 4, 2007, pp. 617–33; Kale Bantigue Fajardo, Filipino crosscurrents: oceanographies of seafaring, masculinities, and globalization, Minneapolis MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2011; Olivia Swift, ‘Seafaring citizenship: what being Filipino means at sea and what seafaring means for the Philippines’, South East Asia Research, 19, 2, 2011, pp. 273–91; Roderick G. Galam, ‘Communication and Filipino seamen’s wives: imagined communion and the intimacy of absence’, Philippine Studies: Historical and Ethnographic Viewpoints, 60, 2, 2012, pp. 223–60.