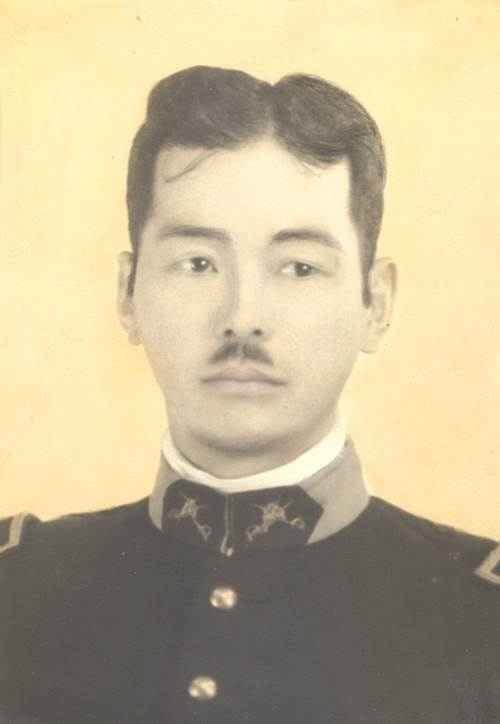

Kingo Nonaka

KINGO NONAKA UN HÉROE MEXICANO QUE NO NECESITO ARMAS PARA SERLO - YouTube

In the early morning hours of March 6, 1911, just a few months into the official start of the Mexican Revolution, rebel forces under the command of Francisco Madero attacked a government garrison in the town of Casas Grandes, Chihuahua about 100 miles south of the US-Mexico border. The initial battle lasted but two hours pitting a ragtag group of insurgents against Mexico’s more regimented 18th Battalion under the command of Colonel Agustin Valdéz. That battalion, consisting of 500 men, was joined by a column of 562 other federales to combat the Madero-led revolutionaries. Attacks and counterattacks continued throughout the day. By the end of the afternoon the rebels, overwhelmed by the sheer firepower of the pro-government Mexican force, decided to retreat to the countryside. When the dust settled, the Mexican government forces had lost 37 men and had 50 wounded. The rebel side had 58 casualties, including 15 Americans who joined the Mexican Revolution on the opposing side. They also had dozens of wounded, and among them was none other Francisco Madero himself who had sustained injuries during a mortar attack. On their retreat through the outskirts of the town of Casas Grandes, a member of the rebel force knocked on the door of a modest home asking for gasoline and alcohol. One of the men who answered the door was Kingo Nonaka, who had been in town for just one day to visit his friend at whose house he was staying. Nonaka asked the man at the door if he could be of help tending to the rebel army’s wounded as he had formal hospital training in Ciudad Juárez. Welcoming the help, the revolutionaries permitted Nonaka to treat their wounded, including their commander, Francisco Madero. Madero was so impressed with Nonaka that he asked him if he would join their army as a medic. Nonaka agreed and marched with the group to Ciudad Juárez where he had lived for the past 4 years. In May of 1911 the rebels under the command of Pascual Orozco and Pancho Villa took Ciudad Juárez and the resulting peace treaty installed Francisco Madero as president of Mexico. The revolution was not over, however, and neither was the role to be played by this unassuming medic, Kingo Nonaka.

In the early morning hours of March 6, 1911, just a few months into the official start of the Mexican Revolution, rebel forces under the command of Francisco Madero attacked a government garrison in the town of Casas Grandes, Chihuahua about 100 miles south of the US-Mexico border. The initial battle lasted but two hours pitting a ragtag group of insurgents against Mexico’s more regimented 18th Battalion under the command of Colonel Agustin Valdéz. That battalion, consisting of 500 men, was joined by a column of 562 other federales to combat the Madero-led revolutionaries. Attacks and counterattacks continued throughout the day. By the end of the afternoon the rebels, overwhelmed by the sheer firepower of the pro-government Mexican force, decided to retreat to the countryside. When the dust settled, the Mexican government forces had lost 37 men and had 50 wounded. The rebel side had 58 casualties, including 15 Americans who joined the Mexican Revolution on the opposing side. They also had dozens of wounded, and among them was none other Francisco Madero himself who had sustained injuries during a mortar attack. On their retreat through the outskirts of the town of Casas Grandes, a member of the rebel force knocked on the door of a modest home asking for gasoline and alcohol. One of the men who answered the door was Kingo Nonaka, who had been in town for just one day to visit his friend at whose house he was staying. Nonaka asked the man at the door if he could be of help tending to the rebel army’s wounded as he had formal hospital training in Ciudad Juárez. Welcoming the help, the revolutionaries permitted Nonaka to treat their wounded, including their commander, Francisco Madero. Madero was so impressed with Nonaka that he asked him if he would join their army as a medic. Nonaka agreed and marched with the group to Ciudad Juárez where he had lived for the past 4 years. In May of 1911 the rebels under the command of Pascual Orozco and Pancho Villa took Ciudad Juárez and the resulting peace treaty installed Francisco Madero as president of Mexico. The revolution was not over, however, and neither was the role to be played by this unassuming medic, Kingo Nonaka.

Besides large influxes of people from the countries of Spain and Portugal during the colonial period, when thinking of immigration to Latin America many people believe it to be a strictly European phenomenon. Italians went to Argentina, Germans went to Paraguay, and so on. Many are unaware of the large amounts of migrants coming from Asia, specifically from Japan, to Latin American countries. Asian immigration began in the middle of the 19th Century with immigrants first arriving from China. This is the reason why in some Spanish-speaking countries to this day Asian people of all nationalities are referred to as “chino,” or “Chinese.” Japanese immigrants started arriving a few decades after the first Chinese migrants blazed the trail for Asians. The south American nation of Peru had a president of Japanese descent, Alberto Fujimori, who was notorious for his harsh crackdowns on communist rebels and his encouragement of massive foreign investment in his country. His daughter Keiko served as a Peruvian congresswoman. Few people know that São Paulo, Brazil, is considered the largest Japanese city outside of Japan with some one million people there having Japanese ancestry, historically mostly concentrated in Bairro da Liberdade, or the “Liberty Neighborhood” of the city. Mexico, too, received waves of Japanese immigrants beginning in the late 1890s during the Porfiriato, or the 30-year rule of Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz.

Besides large influxes of people from the countries of Spain and Portugal during the colonial period, when thinking of immigration to Latin America many people believe it to be a strictly European phenomenon. Italians went to Argentina, Germans went to Paraguay, and so on. Many are unaware of the large amounts of migrants coming from Asia, specifically from Japan, to Latin American countries. Asian immigration began in the middle of the 19th Century with immigrants first arriving from China. This is the reason why in some Spanish-speaking countries to this day Asian people of all nationalities are referred to as “chino,” or “Chinese.” Japanese immigrants started arriving a few decades after the first Chinese migrants blazed the trail for Asians. The south American nation of Peru had a president of Japanese descent, Alberto Fujimori, who was notorious for his harsh crackdowns on communist rebels and his encouragement of massive foreign investment in his country. His daughter Keiko served as a Peruvian congresswoman. Few people know that São Paulo, Brazil, is considered the largest Japanese city outside of Japan with some one million people there having Japanese ancestry, historically mostly concentrated in Bairro da Liberdade, or the “Liberty Neighborhood” of the city. Mexico, too, received waves of Japanese immigrants beginning in the late 1890s during the Porfiriato, or the 30-year rule of Mexican dictator Porfirio Díaz.

In 1897, a minor member of the Japanese nobility, Count Enemoto Takeaki, founded the first Japanese colony in Mexico with 35 farm laborers. The count planned on creating a system of Japanese-owned coffee plantations in Mexico. The scheme ultimately failed but the importation of Japanese labor continued into the first decade of the 20th Century with immigrants shunted to the mines, the railroads or the plantations. The guest workers had contracts with plantation and mine owners that were rarely honored. Most of the Japanese laborers suffered under horrible conditions and many died of tropical diseases or from accidents, such as cave-ins or explosions, in the mines. Many workers abandoned their contracts and left Mexico for the United States or even Cuba. By 1908 the Mexican government ended the system of semi-slavery of immigration under contract and allowed for free immigration from Japan to Mexico. Before World War One only a few hundred Japanese migrants had settled in Mexico under the new terms of free immigration.

The medic of the future president of Mexico, Kingo Nonaka, arrived in his new country with an uncle and an older brother in 1906 under contract to work on an American-owned coffee plantation called La Oaxaqueña in the Mexican state of Oaxaca. Nonaka was 16 at the time. A few months into their contracts, Kingo Nonaka’s uncle died of malaria. After his uncle’s death and fed up with the miserable conditions at the coffee plantation, the teenage boy decided to break his contract and head north to the United States with a small group of fellow workers. It took them three months to travel to the US-Mexico border at El Paso, Texas, with some dying of hunger or from the cold along the way. At the gates to what seemed like “the promised land” Nonaka found himself classified as chino once again, but this time by the United States. He was refused entry into the US under the terms of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 which lumped all Asians together and prohibited them from coming to the United States as permanent residents. Nonaka found himself stuck on the Mexican side, at Ciudad Juárez, not knowing what to do. For months he carried around an old broom and asked people if they would give him food in exchange for cleaning up around their homes or businesses. During this time the young Nonaka slept on a park bench across the street from a church. People noticed him on their way to mass and one day a middle-aged woman intervened. Eventually, a local Mexican family by the name of Cardón took Nonaka under its wing and adopted him, baptizing him José Genaro. Within a year he was operating his own small feed store in Juárez but business was bad and he suffered from constant theft and break-ins, so his adoptive family got him a job at the local civil hospital sweeping up and performing other light janitorial duties. Soon, necessity propelled Nonaka into the role as a nurse’s assistant. With violence along the border increasing and with the Mexican Revolution just starting, Nonaka performed many duties beyond nursing assistant and was essentially acting as a de facto doctor or surgeon at that hospital. He had a solid year of hands-on medical training at the time he was visiting a friend in Casas Grandes and crossed paths with the Francisco Madero rebel group. That chance visit to a friend changed Nonaka’s life and perhaps influenced the course of the Mexican Revolution in the North.

The medic of the future president of Mexico, Kingo Nonaka, arrived in his new country with an uncle and an older brother in 1906 under contract to work on an American-owned coffee plantation called La Oaxaqueña in the Mexican state of Oaxaca. Nonaka was 16 at the time. A few months into their contracts, Kingo Nonaka’s uncle died of malaria. After his uncle’s death and fed up with the miserable conditions at the coffee plantation, the teenage boy decided to break his contract and head north to the United States with a small group of fellow workers. It took them three months to travel to the US-Mexico border at El Paso, Texas, with some dying of hunger or from the cold along the way. At the gates to what seemed like “the promised land” Nonaka found himself classified as chino once again, but this time by the United States. He was refused entry into the US under the terms of the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 which lumped all Asians together and prohibited them from coming to the United States as permanent residents. Nonaka found himself stuck on the Mexican side, at Ciudad Juárez, not knowing what to do. For months he carried around an old broom and asked people if they would give him food in exchange for cleaning up around their homes or businesses. During this time the young Nonaka slept on a park bench across the street from a church. People noticed him on their way to mass and one day a middle-aged woman intervened. Eventually, a local Mexican family by the name of Cardón took Nonaka under its wing and adopted him, baptizing him José Genaro. Within a year he was operating his own small feed store in Juárez but business was bad and he suffered from constant theft and break-ins, so his adoptive family got him a job at the local civil hospital sweeping up and performing other light janitorial duties. Soon, necessity propelled Nonaka into the role as a nurse’s assistant. With violence along the border increasing and with the Mexican Revolution just starting, Nonaka performed many duties beyond nursing assistant and was essentially acting as a de facto doctor or surgeon at that hospital. He had a solid year of hands-on medical training at the time he was visiting a friend in Casas Grandes and crossed paths with the Francisco Madero rebel group. That chance visit to a friend changed Nonaka’s life and perhaps influenced the course of the Mexican Revolution in the North.

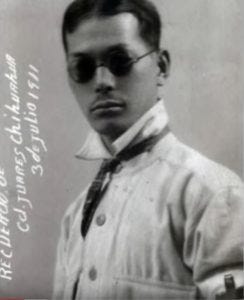

When the rebels captured Ciudad Juárez and Madero became president of Mexico, Nonaka was made head of the nurses at the municipal hospital. With Pancho Villa the head of the Mexican Revolution in the North and with the subsequent unrest after the assassination of Madero, Nonaka found himself in the middle of history once again. Villa asked him to put together what they called a “nursing train” to go with Villa’s army to the city of Chihuahua to tend to the wounded and sick soldiers. Nonaka gathered together the best medical personnel and formed a solid medical team. In an iconic photograph of Pancho Villa on horseback, which has become emblematic of the Mexican Revolution, a young Kingo Nonaka can be seen in the righthand side of the photo driving a hospital wagon. As part of Villa’s army serving in the rank of captain, Nonaka traveled throughout northern Mexico assisting the Northern Division in combating the forces loyal to Victoriano Huerta, the man who assassinated Madero and had taken control of the central government in Mexico City. In total, Nonaka took part in 14 combat operations; 2 under the command of Madero and 12 under the command of Pancho Villa. Villa publicly praised Kingo Nonaka for his loyalty, efficiency and success in treating the many wounded during the war.

When the rebels captured Ciudad Juárez and Madero became president of Mexico, Nonaka was made head of the nurses at the municipal hospital. With Pancho Villa the head of the Mexican Revolution in the North and with the subsequent unrest after the assassination of Madero, Nonaka found himself in the middle of history once again. Villa asked him to put together what they called a “nursing train” to go with Villa’s army to the city of Chihuahua to tend to the wounded and sick soldiers. Nonaka gathered together the best medical personnel and formed a solid medical team. In an iconic photograph of Pancho Villa on horseback, which has become emblematic of the Mexican Revolution, a young Kingo Nonaka can be seen in the righthand side of the photo driving a hospital wagon. As part of Villa’s army serving in the rank of captain, Nonaka traveled throughout northern Mexico assisting the Northern Division in combating the forces loyal to Victoriano Huerta, the man who assassinated Madero and had taken control of the central government in Mexico City. In total, Nonaka took part in 14 combat operations; 2 under the command of Madero and 12 under the command of Pancho Villa. Villa publicly praised Kingo Nonaka for his loyalty, efficiency and success in treating the many wounded during the war.

After the war, Nonaka returned to his duties at the hospital in Ciudad Juárez. His life back to normal, he fell in love with a nurse named Petra García Ortega and married her. The economy in the Mexican state of Chihuahua was devastated after the Revolution, and the Nonakas decided to improve their fortunes by leaving Juárez and heading west to Baja California which was still a territory of Mexico at the time. After spending some time in Mexicali and Ensenada, by 1921 the Nonakas had settled in Tijuana. Kingo opened two photography studios and for many years took photos of everything from Tijuana’s social elites to various street scenes. He had done contract work for the Tijuana police department and was eventually hired as a full-time criminal investigator. Kingo and Petra had 5 children: María, Uriel, Virginia, José and Genero. The Nonakas had a solid middle-class life in Tijuana until history intervened once again. In 1942, under pressures from the Roosevelt Administration in the United States, Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas ordered all people of Japanese ancestry out of Mexico’s Pacific states and territories and relocated them to Mexico City. Kingo Nonaka made the best of his time in Mexico City, pursuing various careers and interests. Not giving up his interest in medicine, he was even one of the founding members of Mexico’s National Institute of Cardiology. In 1977 Kingo Nonaka passed away and the country of Mexico honored him as a war hero and patriot. Among some military historians and Mexican Revolution buffs, because of his loyalty to family, community and nation, and his valor shown in war, Kingo Nonaka has earned the nickname of “The Mexican Samurai.”

After the war, Nonaka returned to his duties at the hospital in Ciudad Juárez. His life back to normal, he fell in love with a nurse named Petra García Ortega and married her. The economy in the Mexican state of Chihuahua was devastated after the Revolution, and the Nonakas decided to improve their fortunes by leaving Juárez and heading west to Baja California which was still a territory of Mexico at the time. After spending some time in Mexicali and Ensenada, by 1921 the Nonakas had settled in Tijuana. Kingo opened two photography studios and for many years took photos of everything from Tijuana’s social elites to various street scenes. He had done contract work for the Tijuana police department and was eventually hired as a full-time criminal investigator. Kingo and Petra had 5 children: María, Uriel, Virginia, José and Genero. The Nonakas had a solid middle-class life in Tijuana until history intervened once again. In 1942, under pressures from the Roosevelt Administration in the United States, Mexican President Lázaro Cárdenas ordered all people of Japanese ancestry out of Mexico’s Pacific states and territories and relocated them to Mexico City. Kingo Nonaka made the best of his time in Mexico City, pursuing various careers and interests. Not giving up his interest in medicine, he was even one of the founding members of Mexico’s National Institute of Cardiology. In 1977 Kingo Nonaka passed away and the country of Mexico honored him as a war hero and patriot. Among some military historians and Mexican Revolution buffs, because of his loyalty to family, community and nation, and his valor shown in war, Kingo Nonaka has earned the nickname of “The Mexican Samurai.”

REFERENCES

De Avila, José Juan. Un samurái en la Revolución Mexicana. In El Universal, 16 May 2015 (in Spanish)

Hernández Galindo, Sergio. “Japanese Immigrants who Joined the Mexican Revolution.” In Discover Nikkei: Japanese Migrants and their Descendants, 7 Nov 2016.

YouTube interviews with Kingo’s son, Genaro Nonaka García.