'Jomon woman' helps solve Japan's genetic mystery

Tuesday June 11, 2019

She had brown eyes, thin curly hair and dark skin that was prone to sun spots. Her earwax was wet and she had a high tolerance for alcohol, even though she never drank spirits.

We know this and much more about a woman who lived and died 3,800 years ago.

All of these details were deduced from her genetic information, meticulously pieced together by a Japanese research team in a breakthrough project of genome sequencing.

The researchers mapped the entire genome of a person from prehistoric times to an unprecedented degree of precision and complexity. What they found tells us not just how she looked, but could eventually answer the question of where the Japanese came from tens of thousands of years ago, and how people lived on the archipelago in the millennia since.

And given that modern Japanese inherited about 10 percent of the DNA present in the woman, she could contribute to an understanding of the diseases and medical conditions to which the Japanese are prone.

A woman from the past

Researchers at the National Museum of Nature and Science and six other institutions launched an anthropological project to investigate the genetic origins of the Japanese. In May 2019, the findings were published in the journal Anthropological Science in a paper titled, "Late Jomon male and female genome sequences from the Funadomari site in Hokkaido, Japan."

During Japan's Jomon period from about 16,000 years ago to 3,000 years ago, people lived as hunter-gatherers. As some of their DNA was passed down to modern Japanese, unraveling their genome is important to understand who the Japanese are and where they come from. This has only recently become possible with the rapid improvements in DNA sequencing technology.

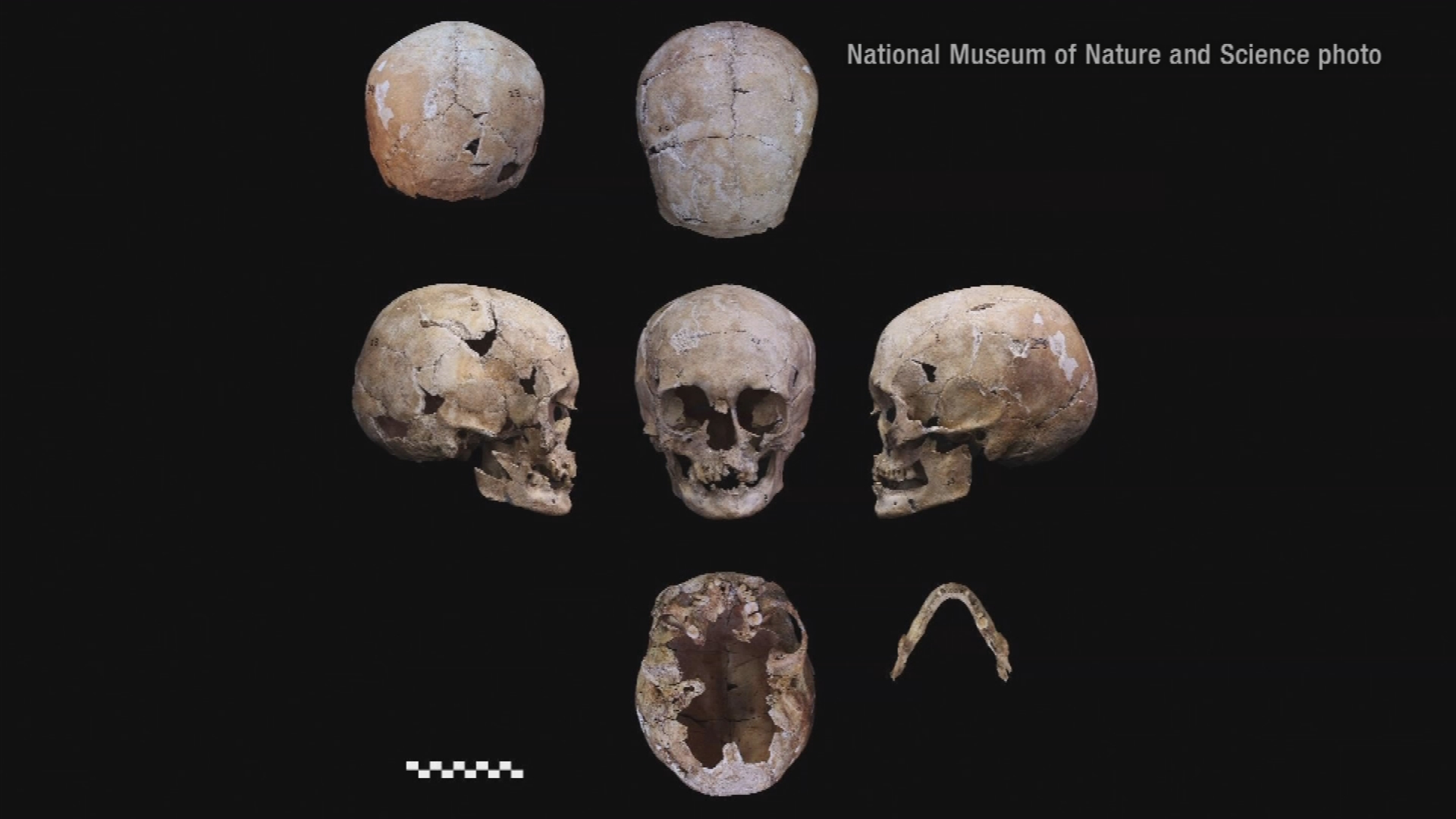

The woman lived on Rebun Island off the northern tip of Hokkaido, the northernmost prefecture of Japan. Her bones were excavated together with those of 27 of her fellow villagers. Researchers discovered that the mitochondria DNA contained in her remains, and those of another male, were in particularly good condition.

The condition of such remains depends largely on the environment in which they were preserved. DNA deteriorates rapidly under warm conditions, so it was fortuitous that the woman came to rest in subarctic conditions.

The researchers proceeded by taking a molar from her skull and drilling a hole to extract the nuclear DNA. The work was carried out in sterile conditions to prevent researchers from contaminating the sample with their own DNA.

Click here to view the original image of 1402x867px.

Previous work on sequencing the DNA of ancient human bones from other parts of Japan succeeded in mapping only some of the genome.

This time, thanks to the perfect sample and the latest technological advances, the team teased out the genetic information of all 300 million pairs of the base sequence. Such complete and precise sequencing of ancient human DNA was an extraordinary feat. The researchers call it a "world first."

In addition to determining many of the woman's physical characteristics, the analysis revealed that Jomon people had a genetic mutation involving amino acids that made it easier to metabolize fat. The characteristic is common among peoples in arctic regions, but doesn't exist among modern Japanese. It is considered proof that the Jomon people were hunter-gatherers.

Where did the Japanese come from?

Based on their findings, the researchers came closer to answering the question of where the Japanese come from. The genetic information of the Jomon woman tells us that her ancestors descended from continental Eurasian people between 38,000 and 18,000 years ago. That means they had a longer period of hereditary isolation than previously assumed.

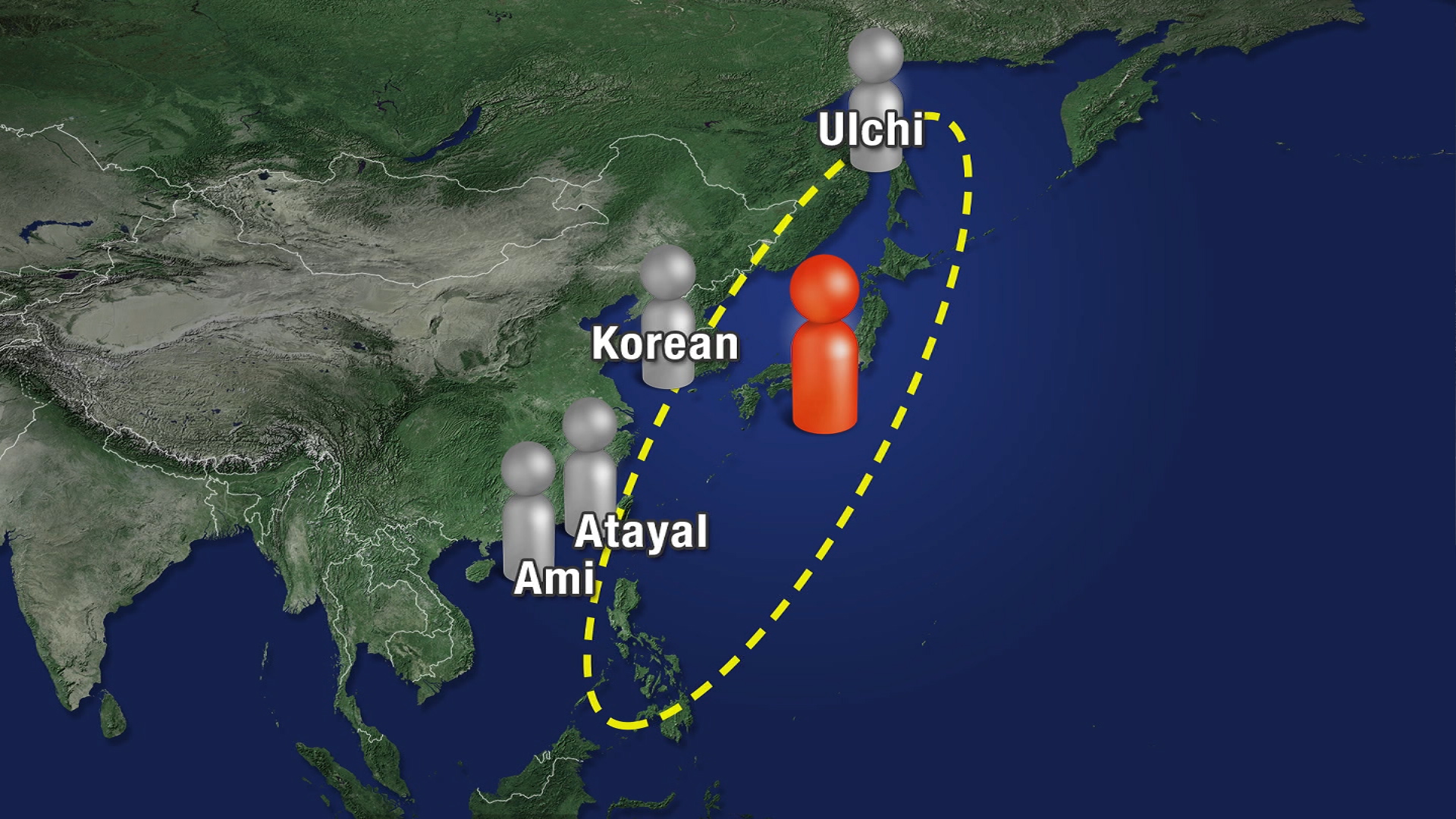

The research also showed that Jomon people shared genetic characteristics with people over a wide stretch of coastal East Asia, from north to south. The woman's genetic makeup has similarities with the Ulchi of the Russian Far East, as well as Koreans and the indigenous Taiwanese Atayal and Ami. These findings begin to add up to a profile of the ancestors of the modern Japanese. They suggest a higher genetic affinity with East Asian coastal peoples than with continental peoples like the Han Chinese.

Click here to view the original image of 1402x789px.

Kenichi Shinoda, Director of the Department of Anthropology at the National Museum of Nature and Science

Kenichi Shinoda with the National Museum of Nature and Science has high hopes for the implications of the research.

"I believe the study of the genes of prehistoric people is set to pick up and leap forward," he says. "The genetic information we have analyzed can hopefully contribute to unraveling the mystery of the origins of the Japanese, or to an understanding of the causes of the diseases to which the Japanese are prone."

For the next phase of the project, researchers will more closely compare the DNA samples of the Jomon woman with modern Japanese over the next four years to find out what further secrets they reveal.

https://www3.nhk.or.jp/nhkworld/en/n...ckstories/555/