Rock tracks or Cart Ruts – they remain enigmatic

Once again I am calling for attention to those archaeological monuments in order to solve the riddle after having struggled more than 40 years with lectures and publications to find a solution to these enigmatic remnants of prehistory. This summary complements my article from 2008.

Description in general

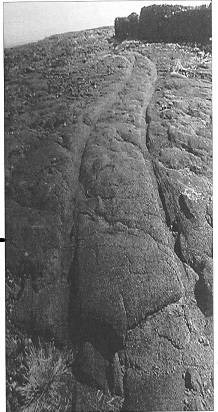

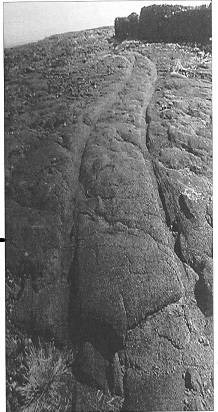

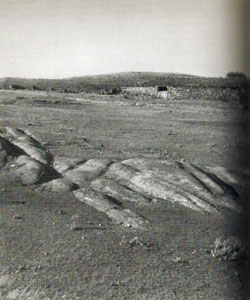

Cart Ruts consist of two parallel tracks runnig through rocky terrain in equal distance. They look like tracks which a chariot has left in soft ground – yet the ground is definitely very solid and the tracks are not fresh but centuries old, to say the least.

During the last decade quite a number of new sites of such Cart Ruts have been discovered, and most people still wonder what the context and the meaning of those prehistoric tracks might be. Therefore I will summarize and enlarge my German publications on this matter for the English reading public.

Rails built in stone or hewn out of rock are not exceptional in antiquity, they were used for carriages to transport statues at religious processions, transport heavy material like stones from the quarry to the building site, etc. Hermann von Pückler-Muskau describes 1836 such rails near Athens. Yet there is another type of rails rarely researched by scientists.

When I first came across those strange tracks in solid rock in Spain in 1972, I was quite baffled and did not find a solution to the enigma right away. Only slowly it dawned on me that they are so mysterious that archaeologists whose task it should be to record and explain them did turn their head the other way rather then venturing into theories without foundation. And this has remained so since the 19th century, I found out. Already in 1877 José Sabater wrote: „These tracks will remain a horror for archaeologists for long time to come.“

Prehistoric they are in some way: Even if they don’t stem back into the Early Metal Age (as I suppose for great part of them) their construction is unaccounted for in general historic records, be they Roman or Medieval although some might have been used until the 18th/19th century. As for their planning and first use we can call them „prehistoric“. And that is about all there is to be said about their age.

Two solutions

As to their way of coming into being I have two suggestions, both standing side by side without excluding each other:

1. They are purposefully worked into the hard rock in order to achieve a fairly good means of getting carts to run over large areas of rocky surface, and

2. they could be accidentally pressed into the soft ground at a special moment and solidified right after the passage of the cart.

I can exclude a third explanation, the one mostly heard when consulting archaeologists: that they are the marks of wearing down the rocky surface by uncountable wheels after long time usage. This is definitely not the case for our Cart Ruts and can only apply to a very small number of short pieces of isolated tracks in agricultural areas, as I have seen in Portugal and Spain where the last two-wheeled carts were still in usage until recently. Those tracks look different and don’t extend to more than a few meters where barren rock is exposed to the open. The individual rails are flat without sharp profile and very wide.

Let us consider the first type:

Perfect engeneering

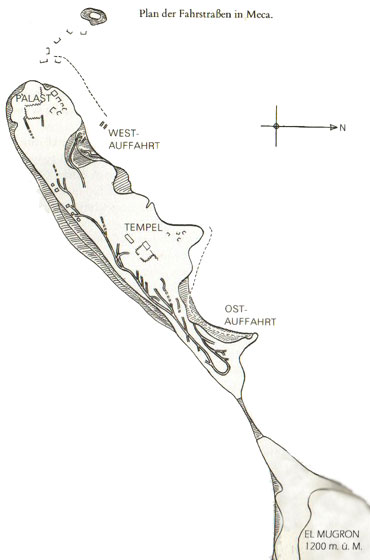

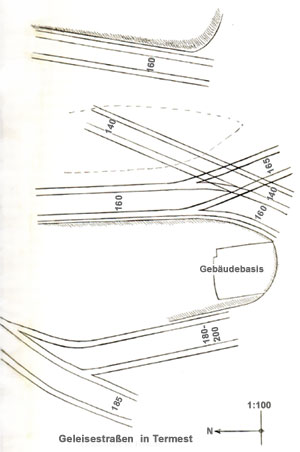

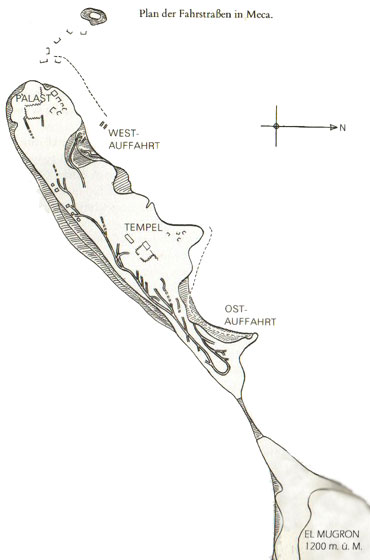

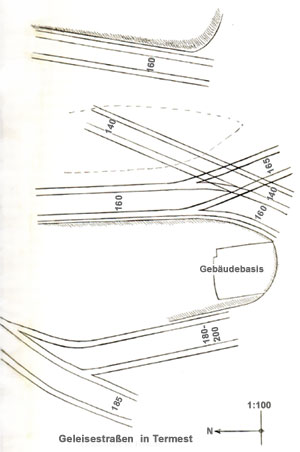

Plan of Castellar de Meca (left) - Fragment of rails in Termancia (right)

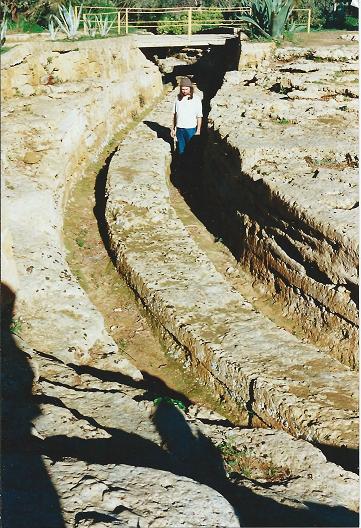

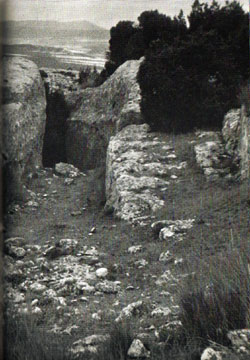

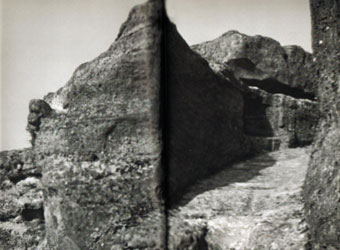

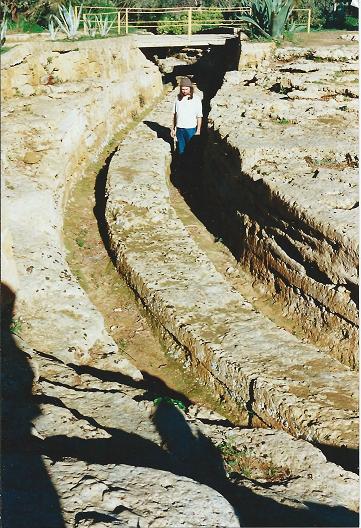

The most outstanding examples I explored are those tracks in Meca and Termancia that belong to prehistoric Iberian sites excavated or at least surveyed officially and well known. The deepest of them go some five to six meters down in the rock, nicely curved and aesthetically worked pleasing the eye. So they are more than just dug into the rock because it was a hindrance on the way up but rather architectonic masterpieces of diligent planning.

(see photos from Meca, Termancia and Cádiz below).

Above: In the surroundings of Termancia - Right: two fotos showing the harbour La Caleta at Cádiz at low tide, with rails

All those passages have in common at the bottom: rails of strictly adjusted width for carts. Sledges could not be used because certain roads bend to a certain angle that inhibits the use of runners. High wheels or a movable axis are necessary.

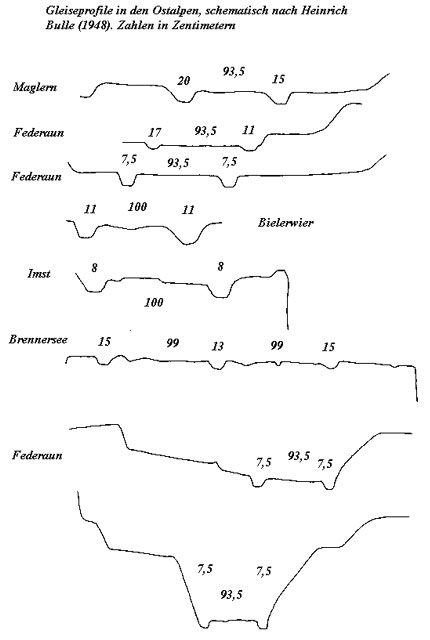

The width of the rails is quite uniform for a great part of those tracks; there are mostly three measures: 180 cm, 160 cm, and 140 cm. The variance is minimal, which means that the same carts could be used in places that lay hundreds of miles apart. It happens here and there that trails of different sizes appear in one location side by side. Best explanation is that they are stemming from different ages. This I concluded from the conservation of the rails: the eldest and therefore most damaged ones are the widest (180-185 cm), while the smallest (down to 110 cm) are the youngest, in some places coinciding with Roman ruins, like in Termancia or Syracuse. In some locations the smaller rail uses one of the elder ones so that only a single new rail had to be worked into the rock.

The system of rails often remains visible over long stretches in the lowlands, riding over barren land and reappearing on blunt rock again, even passing through a small bay of the Sea (Malta). There are branches and switches like at a real marshalling yard as in Claptham Junction (Malta). One can even imagine one-way traffic at certain places like in Meca, one for driving up, the other way down.

Assuming that carts with high wheels were used on those tracks, it is uncertain what had been transported. At the first site I inspected, the Cueva del Rey Moro at Meca in Valencia (Spain), I saw deep holes in the rock of reddish colour supposing that iron ore had been found here and transported to the town on top of the rock for melting and casting. I found basins and structures in the rock suggesting working places for steel manufacture. The other location in Spain, Termancia, was until Roman times famous for its excellent steel blades and swords. If we find no ore there any more then it might be due to complete exhausting the caves because this type of meteoric ore, presumably fallen from heaven and embedded in the lime rock, had a high content of precious minerals that made it most valuable.

At Malta near one end of the trails there are caves which could have yielded ores.

Yet, in general, nothing is known about possible use or intention of the Cart Ruts.

2nd explanation:

Catastrophic event

This interpretation is only good for some locations which don’t look like being planned or worked with care but rather stem from accidental happenings, used once at certain moments of fear or desaster. This seems to me the only explanation after thinking long time about those tracks which are distributed without system rather hazardly on even rock surface. They look like marks in snow or swampy ground crossing each other at strange angles without making sense. This is especially the case for some Cart Ruts at Syracuse and for some on the isle of Malta. They are not worked by chisel into the rock nor are they used several times. The rock must have been soft and got hard within short time. One sees remnants of rock in the trails which could not remain if the rails had been intentionally hewn out for a carriage to pass; at least this hindrance in the rail would have long been worn off by wheels if they had used this rail many times.

One sees here and there unique rails, the second one missing, which I interpret as a shaky movement of the cart: it nearly toppled over, one wheel hanging for a moment in the air. Equally noticeable are tracks very near side by side: the second axle or a following chariot did not glide in the same trace as the first one because it was rolling on the slippery ground. There is even a mark of two wheels that suddenly get near to each other and then stopping altogether, as if an accident was pressed into the ground: the axle broke and one wheel got loose striving in direction of the other wheel before the chart broke down (at Syracuse).

Of course, not all marks can be understood in this actualistic manner. At certain places we find a strong gradient between the two rails. If a chart would have pressed them into the ground, it would have toppled. The only explanation here is that the rock had been moved by seismic activity after the rails were used. This must be the case when we see a track suddenly ending because the rock has broken off and fallen down a ravine or into the sea.

(photos LK from Malta)

The scenario for such wild tracks as in Syracuse is somewhat difficult. I suppose that a widespread civilisation in the early Metal Age used two-wheeled chariots for transport and pleasure as well as warfare all over Europe and well into Central Asia (see Topper 2003). At a certain moment a catastrophe of cosmic origin destroyed this civilisation and covered the remnants with debris. Only some of the sites are openly visible showing their technique and ability to build roads and tracks. This is the case for Termancia and Meca. Others are excavated, and some are still hidden,

At the moment of desaster people tried to flee using their chariots and thus drove their tracks into the molten ground. At Malta, Syracuse, and other sites we get an idea of this last struggle to escape destruction. (photo UT from Syracuse)

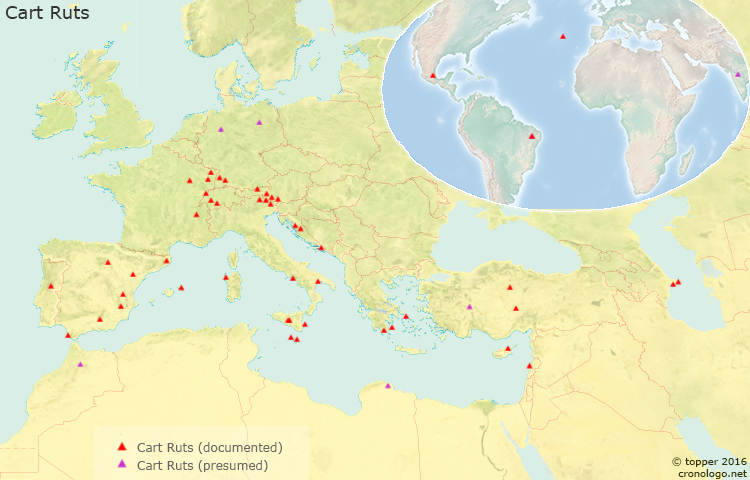

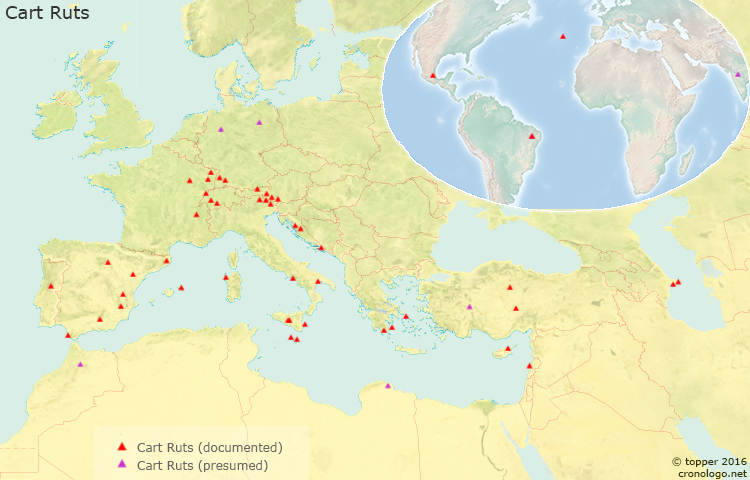

Dispersion

In order to give an idea of the wide dispersion of the Cart Ruts in Europe I have started a list of known sites which by all means is incomplete. The map will continuesly be adjusted to latest discoveries.

Central Europe

Central Europe

Mohrinisches Feld (Brandenburg), mentioned in 1751 but vanished since, this site is rather dubitable.

Externsteine, excavated by Ewald Ernst (actual), not tipical, of minor width.

Two new sites in Southern Germany, just discovered, made known by Thomas Horn in 2015:

Albstadt (Swabia)

Kniebis (Freudenstadt, Black Forest)

Our colleague Helmut Ruf verified this new site recently in March 2016:

In Summer 2016 I saw the fragment at Kniebis and discovered a second piece some kilometers off:

.JPG)

Recently Helmut Ruf discovered another fragment in the Black-Forest at the Celtic settlement Kapf (Schwenningen). The two photographies show faint ruts on the rocky surface:

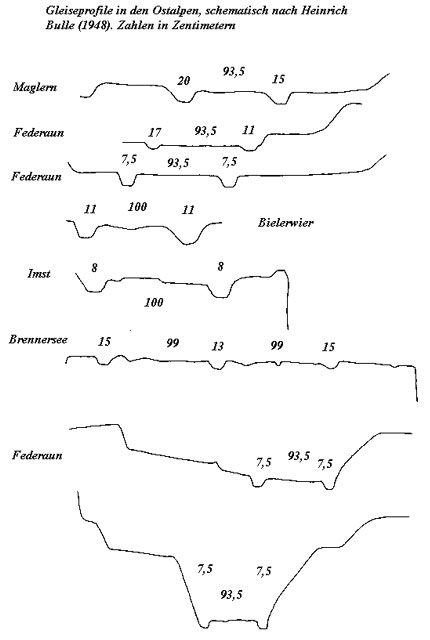

Known since half a century are the ancient roads in Switzerland and Eastern France, Austria and Croatia, traversing the Alps and other mountain ranges, a whole bunch of tracks from Roman times and later, published excellently by Heinrich Bulle, Geleisestraßen des Altertums Sitzungsberichte der Bayer. Akad. d. Wiss., 1947, Heft 2, Munich 1948. Here a list of some profiles of those tracks, the numbers refer to measurements in centimetres.

For Frinvillier, Berne, Switzerland, see Pfister 2004 ( http://www.dillum.ch/html/toise_de_saint_martin_frinvillier.htm). There the tracks end abruptly at a cliff.

More "Roman" cart ruts are described by Helbling, Hanno und Moosbrugger, Bernhard (1972): Roemerstrassen durch Helvetien (Pendo, Zürich)

At Heidenstadt near Saverne (Zabern) in Loraine (France) an old track is paved with slabs (photography by the author)

Another one is at the famous Odilienberg (Alsace, France)

And also in France: at Anse de St. Croix near Marseille, a good bunch of tracks near a quarry.

Ireland (2011) location not known

Spain

Mainly four sites I discovered and described (published 1977):

Termancia or Termest (Soria)

Castellar de Meca (Valencia)

Castelillo de Alloza (Teruel)

Cádiz, under water.

This last site is not always visible because it lies in the small port of La Caleta open to the ocean and is covered most of the time by the sea. Only at low tide it can be visited. The length of the rails amounts to ca. 100 m, the width is 160 cm. There are several fragments, all leading to the higher part of the rock now under the pavement of the town.

New sites have been discovered since, not yet visited by the author:

Los Molinos at Padul (Granada) called Roman road - see the new foto of Christoph Ehlers 2016 here:

Solana de la Pedrera (Murcia)

Peratallada (Girona) – about 22 km east of Gerona near Toroella de Montgrí, not far from the Mediterranean Sea, photo 2014

Menorca (Baleares)

and Mallorca: near Cala Millor on the way to the Castle, photographed by Erwin Wedemann 1998 and handed to me in 2000. In his letter Wedekind writes that no sign of cissel can be found, neither are those tracks testifying to long time use but rather suggest strongly by their sharp edges that they have been left in a single happening (see 4 photos below).

In Portugal a new site has been noted:

Chas de Egua at Piódao (Serra Estrela, Prov. of Coimbra)

and moreover: tracks on the Island of Terceira (Azores).

There are good fotographies of both sites in Portugal : http://www.ancient-wisdom.com/portocartruts.htm. The authors make it clear that the tracks on the Azore-Islands are "pre-christian", will say: from before the Portuguese discovery of the isles.

Recently Holger Kalweit has published a remarkable series of 16 fotographies of the tracks on the Isle of Pico (Efodon-Synesis 1/2018) of which I chose one (alas without measurements):

(Foto Holger Kalweit 2017)

This track is more than 1,5 km long! Some of the tracks vanish into the sea, just like in Càdiz or Malta. If we thought so far that the Isles were visited only off and on by chance of some boats, it becomes evident now that there must have been a durable contact of the settlers to the continent, otherwise the cart ruts here make no sense.

Quite a number of tracks have been found in Italy,

discovered 1999 and published from 2002 onwards by the author.

Here is a second foto from Syracuse (Sicily), where the tracks are found all around the city (1999):

Agrigent (Sicily) at the temple 1999 (foto below)

Matera (Apulia) 1999 (foto below)

Not far from Matera, at Alessani in Lecce (Apuglia), the tipical ruts are found near the sea, called "solchi" in Italian.

At the volcanic terrain around Pitigliano the situation is a bit different as the rock is very soft (tuff) and therefore easy to cut.

Pompey, again, is a bit different as the tracks are in the streets of the excavated town (foto below).

The „Cart Ruts“ of Sardegna are hardly known in general although they are found alongside with archaeologically well explored and published tombs of neolithic or early metal age, at the site of Su Crucifissu Mannu near Porto Torres at the northwestern tip of the isle.

Here a foto by Hartwig Hausdorf (see: www.hartwighausdorf.com) who compares them to similar ruts on Malta, less impressive than Clapham Junction but bigger than Bingemma.

Another foto of the same site was taken by Gianni Careddu on Mai 19th, 2012, and published on wikimedia commons. I deem it important that sombody should measure those tracks and explore their whole length!

On the islands Malta and Gozo there are many "Cart Ruts" ,

wellknown and cartographed (see my article 2008  and the website of Cihla Vaclav).

and the website of Cihla Vaclav).

Tracks in Turkey

were found in 2000 by the author: at Metropolis (Afyon), an ancient Christian ruined town hewn out of the rock (no photo on account of bad weather).

Now I just got notice of a very remarkable site near Afyon-Karahisar, shown in a video at You-Tube (www.lah.ru). It is located about 30 km north of Afyon and has some features that are nearly unbelievable: streaks at the sides of the tracks as if caused by the nave of the wheels and even higher up by the structure of the vehicle. The width of the tracks is medium (around 140 cm from the outside edges), but up to 50 cm deep. They look like imprints of carts left in soft soil and petrified soon after.

At Derinkuyu (Nevşehir), rails were found by Tatjana Ingold 2004 and published at the end of my article in "Sagenhafte Zeiten" (2004, no. 5, p.32). There are four fragments on the left side of the road from Derinkuyu towards east to Basköy, about 6 km before Basköy.

At Yazilikaya (Bogazköy), old Hitite town, several fragments of ruts have been mentioned; we did not find them.

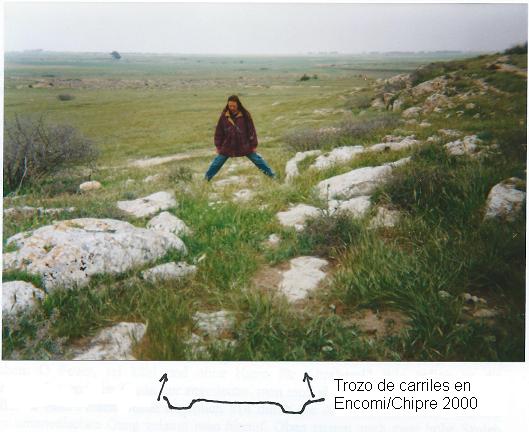

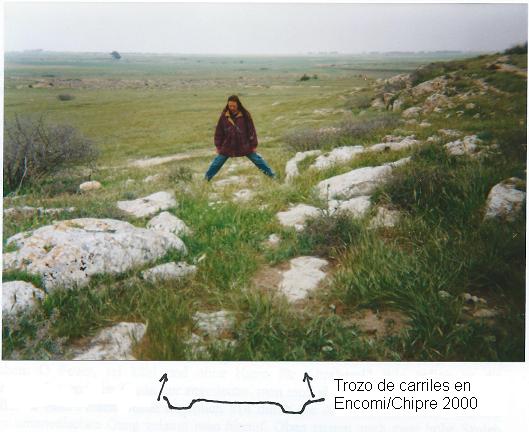

Northern Cyprus: Encomi, a Bronce Age town excavated by Claude Schaeffer. We found only a short fragment of rails, see foto: The person indicates the width of the rails, the drawing at the bottom gives the profile.

Another piece of rails on Cyprus was reported to me in 2000, it had been been found near Famagusta at Paralimni in 1981.

Recently the magazin Efodon-Synesis 4/2016 (pp 19-21) published an article with photos of Ferdinand W. O. Koch, who found the typical and inexplicable ruts in the Roman Bath of Beirut in Lebanon. He comes to the same conclusion as we above: "The terrain makes such an impression, as if everything had been set in motion and then solidified abruptly, or petrified." From his description it is also apparent that the Roman Bath was built much later than the ruts, and that they don’t make sense in this structure. Unfortunately, the dimensions are not reported by Koch, but he draws attention to the extra edge that runs along the top of the track which we, too, saw in several locations, and which cries out for explanation.

The following sites are at the edge of the Caucase in:

Azerbeijan

Two sites near Baku at the Caspian See: Türkan (40.38 N – 50.21 E) and Süvalan near the coast.

Apsheron Peninsula and Beyuk Zire (former Nargin) Island in the Baku bay.

And even in India: In 2002 Franz Brätz published in his book "Indische Geisterstädte" (Schlotterbeck, Marktoberdorf) the site of Rajagriha in Bihar, where a wall of stones of 1-1.5 m length, up to 4 m high, 40 km long, issues from the southern gate, alongside which there are cart ruts of 1.5 km length which look like having been cut into the volcanic rock with a knife into soft cheese. The town is known for having hosted the first buddhist council; Siddharta as well as Mahavira are said to have lived there.

Mexico

Tlaxcala de Xicohténcatl, north of Puebla, photos by Josef Otto.

Brasil

Sousa in Paraiba; in the same region there are many petrified imprints of dinosaures.

Those sites of "Cart Ruts" in America are intriguing as academic teaching insists that the wheel was unknown in pre-Columbian America.

January 2019

Again cart-ruts have been discovered in places where they were not expected:

now in the USA !

One site in the Southwest of the states is called White Cliffs Trail. It shows deep traces in the ground beside the trail in regular distances for which I cannot imagine any reason. You find them on a website that deals with the cart ruts as well as other megalithic sites of the type we have wondered about (like huge walls or unexplainable techniques of stone cutting):

http://megaliths.org/browse/category/27/view/751

The other site in the US is called "Curious Historic Tracks at Bull Creek", Austin, Texas,

http://megaliths.org/browse/category/27/view/803

There is even a video to it

video :

where you can see two pairs of tracks that are partly superposing one into the other in precise distance.

Dana Williams/KPRG

Dana Williams/KPRG

.JPG)