The Aztecs and the Mayans are both attributed to being some of the oldest civilizations in North and Central America. While the Mayan timeline goes back further than that of the Aztecs, both were renowned for their architecture and modern contributions to their societies.

Today, ruins from both the Aztecs and the Mayans can be found throughout places such as Mexico. This is also where one will find the most visited of all their pyramids and ancient cities, which can be confusing when it comes to knowing the significant differences between each civilization. Before visiting the ruins of either one, here are some key differences to note in both their architecture and their cultures.

The Mayans: Known For Their Incredible Pyramid Architecture

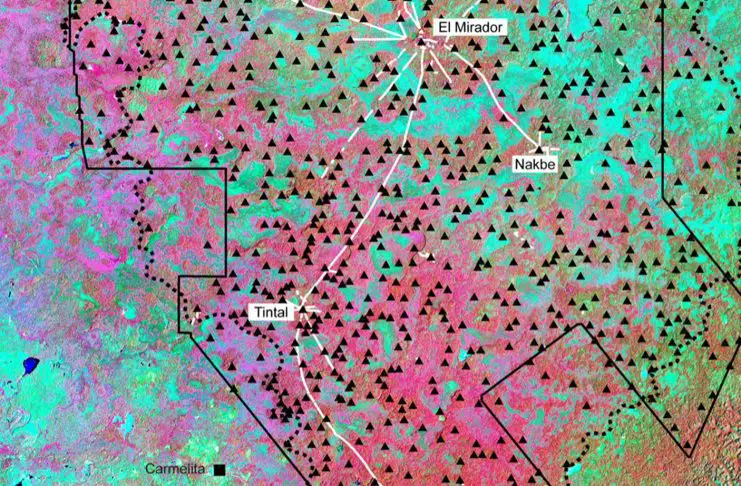

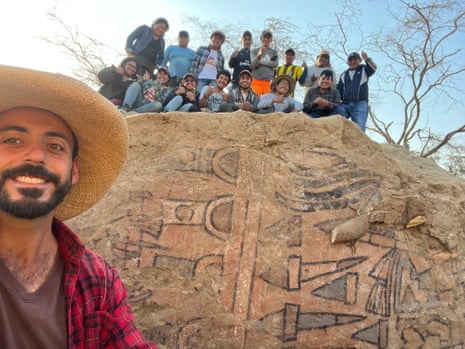

When one thinks of Mayan ruins, it's common to picture pyramids. The Mayans were known for building incredible structures like these in many of their city-states, many of which are still standing to this day. The most notable difference in architecture throughout the Mayan pyramids can be seen in the stories that they tell, which have been done through a myriad of pictographs and statues, all telling of their gods and beliefs.

Those visiting Mayan pyramids will notice two distinct styles: those which were built for religious worship, and those which were built for gods. The former would usually include a temple at the top which would be used by Mayan priests during ritualistic practices, while the latter would be used for the strict purpose of honoring the god for which it was built. These would also have stairs that were far steeper than that of the religious pyramids, with the likely intention of keeping most people out. Additionally, these are also the pyramids that featured tunnels, trapdoors, and secret doors within.

The Most Famous Mayan Pyramids

- Pyramid of Kukulkan (El Castillo), Yucatán, Mexico

- Tikal Temple I, Guatemala

- Temple of the Inscriptions (Palenque), Palenque, Mexico

- Pyramid of the Magician, Uxmal, Mexico

- Caana Pyramid, Belize

Additional Features In Mayan City-State Architecture

While the pyramids that the Mayans built had very serious connotations, not everything discovered in their city-states did. Some even had ball courts, which were recognizable due to their smooth floors and rock walls, mimicking that of today's stadiums. These could be attached to temples or located within the city and were used for sporting events.

Additionally, the Mayans also built grand palaces for the king and his royal family. The best example of this, according to Ducksters, is the palace at Palenque, which was built by King Pakal. This palace, alone, was built with several buildings within its complex, as well as a courtyard and an overlook tower.

RELATED:Long Before The Aztecs, This Ancient City Was One Of Largest In The World (And It's A Day Trip From Mexico City)

The Aztecs: Known For The Empire They Built Within Mexico

It is easy to confuse the two civilizations, especially since many Mayan civilizations did live in Mexico and overlapped with the Aztecs. However, the Aztecs lived almost exclusively in Mexico, which is how they were easily differentiated. Later evidence suggests that they lived in Belize, as well, according to Diffen.

- Fact: Legend has it that the Aztecs settled in Mexico, specifically Lake Texcoco, after seeing a vision that instructed them to do so.

Similar to the Mayans, the Aztecs were known for their pyramids. However, there are far more Mayan ruins still in existence to this day than there are Aztec ruins. Since the Aztecs ruled a trio of cities - Tenochtitlan (modern-day Mexico City), Texcoco, and Tlacopan - this is also where the best-known remaining site of their ruins stands. Templo Mayor can be found in Mexico City, and it was once the location of one of the main temples in Tenochtitlán. Visitors to Mexico City can also find two of the most iconic Aztec pyramids - the Temple of the Moon and the Temple of the Sun - just outside the central region of the city; this is also known as the Teotihuacán (a Mesoamerican center not built by the Aztecs).

The Aztec pyramids are considered to be a classic example of early Mesoamerican architecture. These were structured in a fairly simple manner, with one main core of rubble that was held in place by what is known today as retaining walls. After this foundation was created, the pyramids were then laid with adobe bricks, and covered with limestone. As a result, the Aztec pyramids were flat on the top, featured large, wide steps, and were notably short compared to other pyramids around the world. Similar to the Mayans, the Aztecs often built temples on the flat tops of their pyramids.

Those visiting both Mayan and Aztec ruins in Mexico are in for an incredibly historic experience. While much can be learned prior to visiting, sometimes, knowing the basics of ancient architecture can give one a full appreciation for the civilizations that built the land on which travelers stand.