Most people think of ao-dai as the traditional attire of Vietnam, but not many realize that the tailoring of ao-dai today is drastically different from the tailoring of ao-dai in the early 20th century and earlier.

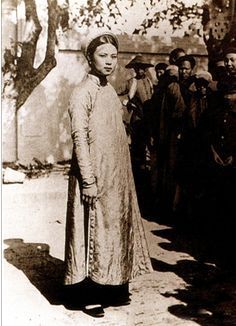

Early modern ao-dai followed the tailoring techniques common in the Sinospheric countries. Two pieces of fabrics were sewn together at the body midline, forming the front flap, and same for the back flap. Often an attire was made of two layers of fabrics stitched together (in the case of Japan, four layers, that's why kimonos always looks thicker than attires from Korea, China, or Vietnam). Some features distinguishing early modern ao-dai from its modern counterpart:

1) The shoulder line of early modern is straight when spread out.

2) The armpit area of early modern ao dai is wide regardless of whether the sleeves are narrow or loose (this was because people back then often wore more than one layer of clothes, the wide armpit area was to accommodate the many clothes they wore).

3) From top down in early modern ao dai, the body piece always gets much wider. In modern ao dai, the body is almost straight from top down.

4) Early modern ao dai did not have raglan sleeves like modern ao dai.

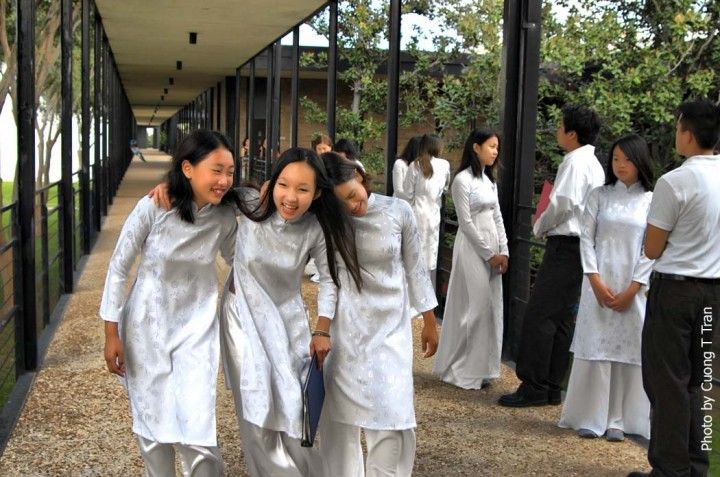

Modern ao dai has been influenced by tailoring techniques from the West

Modern ao dai spread out

Early modern ao dai spread out (20th century). Technically it should be called "áo ngũ thân" - the progenitor of what we call ao-dai today.

A variation of áo ngũ thân with wide sleeves. 20th century, Nguyen dynasty, Vietnam.

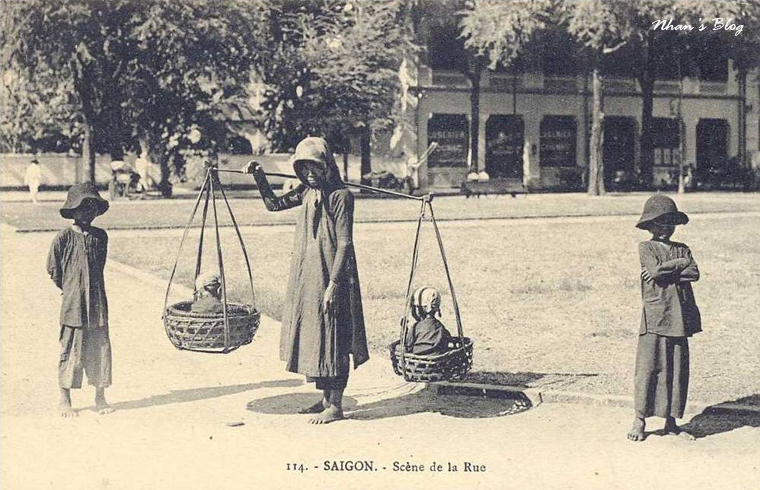

Early modern aodai was similar to earlier attires in term of structure

From top down: 1) 18th century cross-necked robe (called áo giao lĩnh) of Lê dynasty, Vietnam. 2) 20th century imperial attire of Nguyễn dynasty, Vietnam. 3) 18th century round-necked robe (called áo viên lĩnh) of Lê dynasty, Vietnam.

Nhật Bình jacket of Nguyen dynasty, Vietnam.

Nguyen dynasty ceremonial robe

Nguyen dynasty mandarin robe

Nguyen dynasty mandarin robes