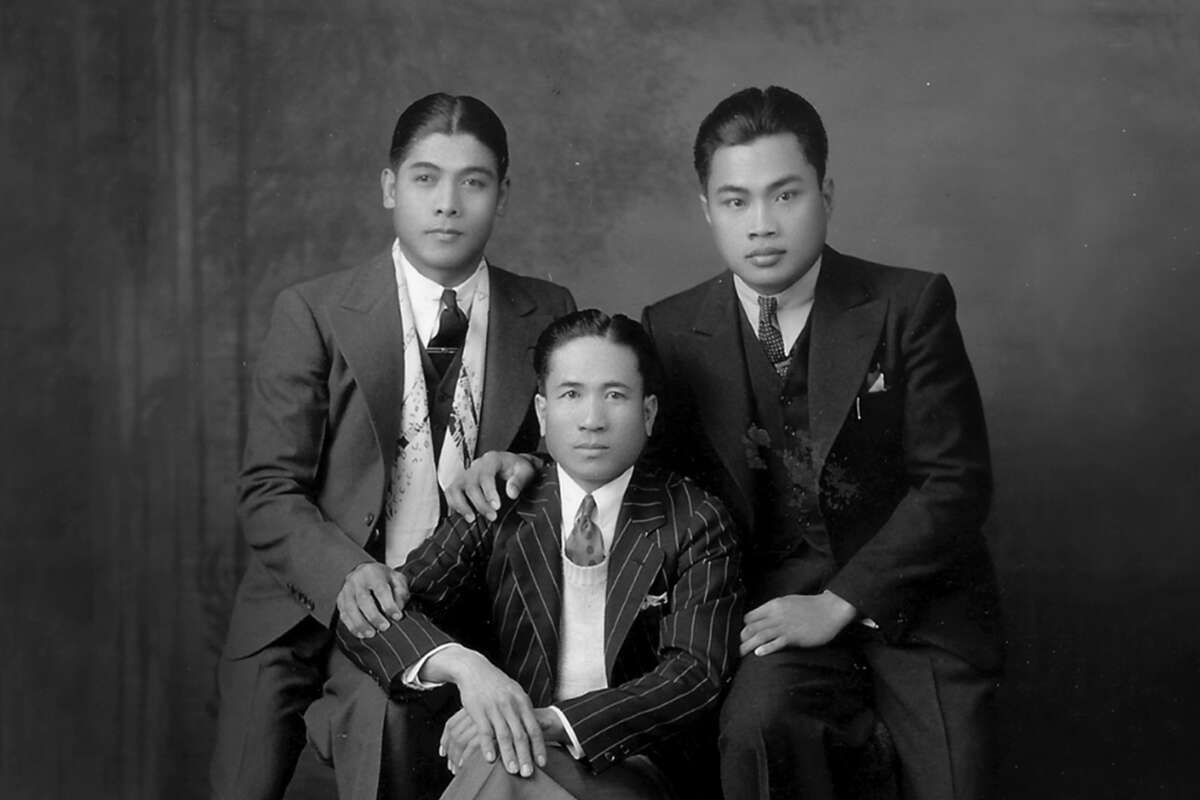

A picture of Anita Navalta Bautista's husband Cornelio (right) with two of his cousins in the 1930s.

Courtesy of Anita Navalta Bautista

Jerry Paular fondly remembered the Filipino farmhands he grew up with. They were so well-groomed and well-dressed, he said, that “you would think they were movie stars.”

“They wore suits that were just unbelievable,” Paular, a traveling suit salesman, once recalled. “They would never go to a store and buy a $20 suit and hit the streets. These guys came out looking like movie actors. And yet, they were common laborers.”

At that time, Macintosh Studios was the pinnacle of Hollywood style for men.

The bespoke suitmaker, whose main shop was on 222 Powell St. in San Francisco, opened in 1922. It served as the in-house designer for many of the big Hollywood studios in the 1930s, worn by the likes of pre-Hays Code stars such as William Powell, George Raft and James Gleason.

But the suits, and Filipinos' defiant appropriation of white Hollywood aesthetics, soon drew the ire of white Americans, with fatal consequences.

“Macintosh Studios was the premier high-end Hollywood tailor of the era,” Roberto Isola, a vintage suit collector in South San Francisco, told SFGATE. “Every aspect of the construction, the materials that they used … they’re basically pieces of art.”

Not much is known now of the suits’ provenance, even among vintage collectors like Isola. But these weren’t the slim-fitted, super-conservative and formal tuxedos so often associated with Roaring Twenties-style menswear.

Longtime Chronicle columnist Herb Caen once described the trademarks of a Macintosh suit: “In the days when S.F. was chockablock with show people, the Macintosh suit was a legendary trademark — huge padded shoulders, drape shape, nipped-in waist, highrise pants with deep pleats.”

The suits were made out of supple wool and fine silk, and had flourishes rarely included in off-the-rack suiting — like an auxiliary pants zipper that could be undone after an especially heavy supper, or triple darts on the jacket to provide better contouring around a man’s figure. Pre-Hays Code fashion leaned toward what Isola referred to as an “exaggerated look,” with full lapels and broad ties to match.

A series of advertisements published in the Los Angeles Times and the Chronicle in the early '50s sought to capitalize on the brand’s legacy of dressing pop culture royalty. Figures like Jack Bailey, the stalwart host of the long-running game show “Queen for a Day,” and ventriloquist Edgar Bergen, father of Candice Bergen, wore these suits, the ads proudly boasted. To wear a Macintosh suit, the ad copy reasoned, was to own a little sliver of Hollywood regalia, a little taste of the spoils of fame.

1952 ad for Macintosh Studio published in the San Francisco Chronicle.

“They know that a Macintosh suit wins regular applause from men who value appearance,” one ad read.

Another advertisement published in a 1953 New Yorker issue crowed that MacIntosh “tailored over 41,400 suits for ladies and gentlemen in northern California.”

These advertisements, in claiming a well-to-do, A-list pedigree, glossed over a small but vital clientele: Filipino laborers in the Bay Area and Northern California.

‘They wanted to be smart’

In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Filipino men desired bespoke suits out of sheer necessity. Off-the-rack suits available at the big, mass-market department stores like The Emporium, Montgomery Ward or Sears didn’t fit the standard Filipino stature.

The suit jackets sold in stores ran all the way down the average Filipino’s knees, recalled Anita Navalta Bautista, a self-described mestiza historian who was born in 1933 during the height of the Great Depression.

But once the Macintosh suit entrenched itself into the collective psyche of Filipino American men at the time, the fit was entirely beyond the point. The suits were worn as a small act of defiance, as if to steal a little taste of American luxury, to lay a tiny stake to the privilege of white, upward mobility in America.

The Philippines was taken over as an American colony in 1898, following the Spanish-American War, which resulted in a yearslong war between Filipino nationals who wanted independence and the American military. But starting in 1906, still reeling from the effects from the Philippine-American War, Filipino men began emigrating to America.

They were sought after for cheap farm labor and not subject to anti-Asian migration laws because of America’s colonial relationship to the Philippines. Filipino men at the time, however, were unable to own property and did not have any path to citizenship due to their colonial status.

American “teachers” in the Philippines also encouraged them to come to America, promising wealth and opportunity galore.

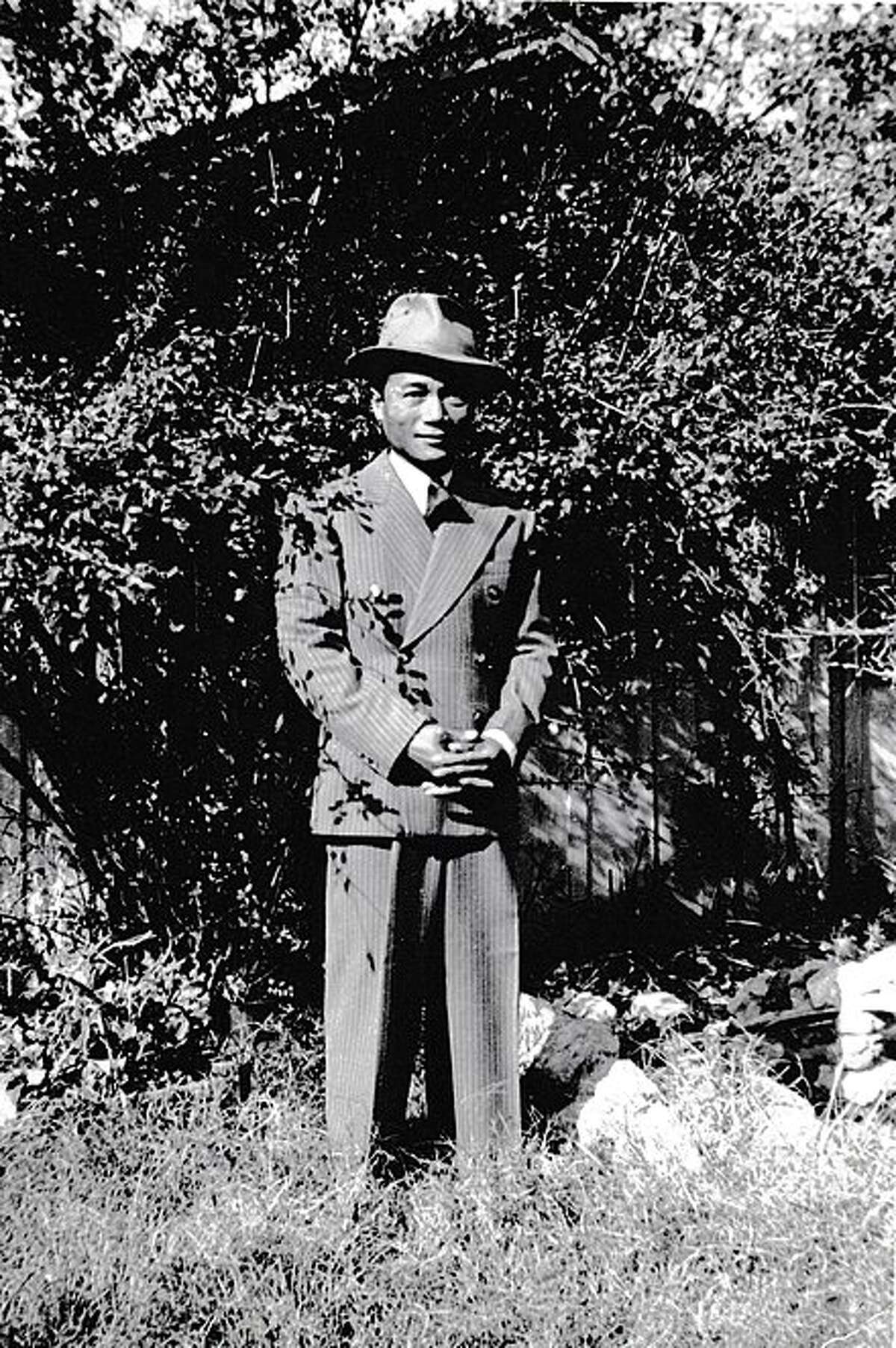

A Filipino immigrant in California, circa 1941, wearing the fashion of the era.

Archival / Unknown

Thousands, mostly men by a ratio of nearly 14 to 1, emigrated. By 1930, there were more than 30,000 in California.

And for many of them, the name Macintosh was synonymous with the finest suits, to the point where many would use the term “Macintosh” to refer to all of their suits — even the ones not made by the Macintosh brand itself. (In many first-person memoirs and other accounts by Filipinos, they’re more commonly referred to as “McIntosh suits,” sans the “A.”)

Bautista recalled that the suits cost about $100 back when her husband Cornelio, a musician at a taxi dance hall, would travel to San Francisco and get them custom-made for his performances.

Paular, the salesman, was employed by Macintosh to travel down to Filipino neighborhoods in Central and Northern California and get their measurements so that the suits could be made back on Powell Street. Other tailors in San Francisco, including one by the name of Sommer, advertised suits specifically to Filipinos.

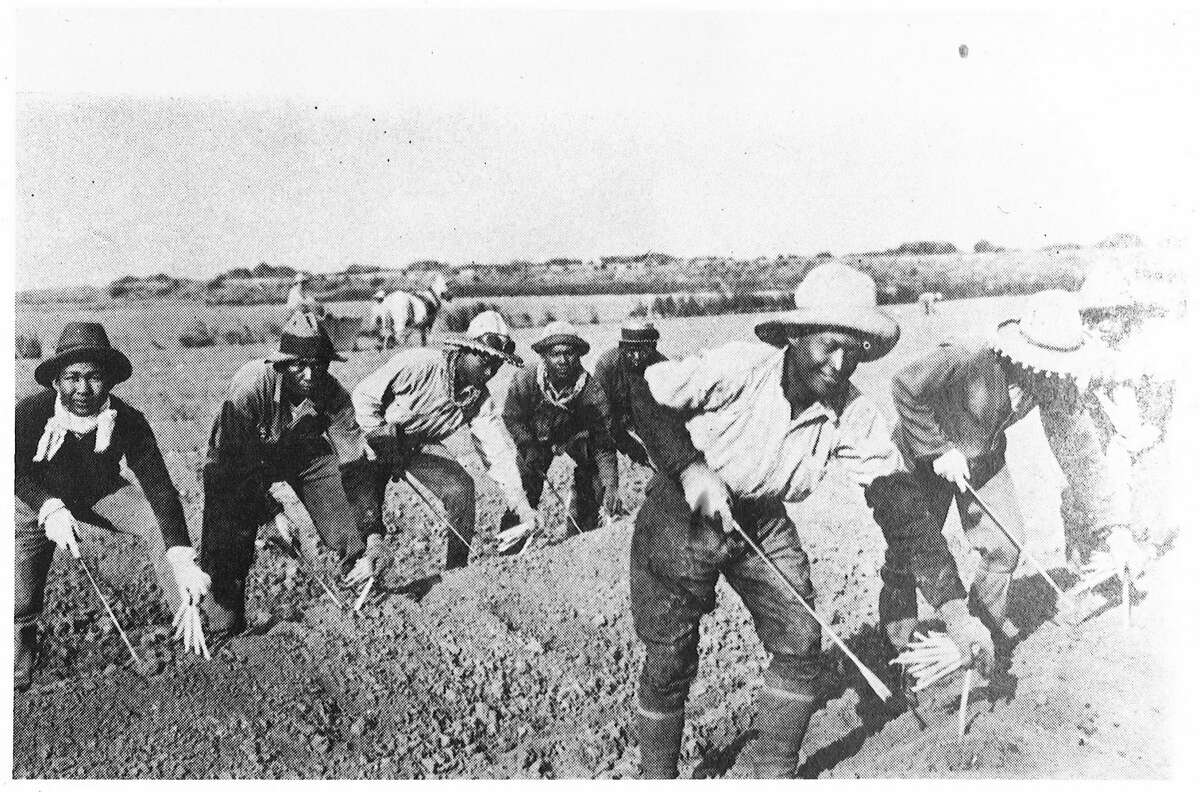

The men were subject to degrading conditions and low pay at work. They most commonly worked as farm laborers, picking lettuce and asparagus in the dry California heat. Some Pinoy farmworkers were paid 90 cents a day for their work, less than half what their white counterparts earned on the fields.

One Chronicle article from 1930 reported that 80% of all asparagus pickers in the state were Filipino.

Those conditions didn’t matter on their days off.

Barkada, the Tagalog word often used for “friends” that symbolizes a communion closer to brotherhood, would go to taxi dance halls, gambling dens and pool halls to unwind from the demeaning conditions of their work.

These manongs — a word in Ilocano, a native language in the Philippines, meaning “eldest son” but used in 1920s parlance to refer to these young Filipino bachelors — wore their finest Macintoshes for every leisurely activity.

With a Cuban cigar in their lips, their slicked-back hair covered by a Stetson hat and their suits perfectly tailored and pressed, they looked every bit as debonair as the leading men they religiously watched on the silver screens.

In a comprehensive account of Filipino men's style and consumer habits, the Filipino historian Mina Roces contended that their desire to emulate the dandiacal aesthetics of Hollywood leading men was an effort to “achieve the white masculine ideals touted by Hollywood movies of the time, and to communicate success to relatives back in the Philippines.”

These suits telegraphed a status and wealth that belied the backbreaking toil of their day jobs. It didn’t matter where you came from, or what work you did, if you looked like money.

“They wanted to be smart and wanted to wear the most expensive suits, but remember, Filipinos at the time in the 1930s were sending their money back home,” Bautista told SFGATE.

Men would go to photo studios to take pictures, often in groups of three and four, in an effort to uphold a facade of spoils and success available in America. These photos, along with remittance payments, would be sent back to the probinsyas and baryos they left behind in the Philippines.

The photos are all uniformly stunning. Handsome men, dressed to the nines, became representatives of a dream to be realized in the country that colonized them.

The taxi dance hall, a 'den of iniquity'

A view of San Francisco's Pacific Street in the 1930s, featuring the Barbary Coast club, the unofficial flagship of the area that also featured numerous other clubs and bars.

Frederic Lewis/Getty Images

The most common place Filipino laborers wore their suits was to the taxi dance halls, something of a precursor to seedy nightclubs that originated from San Francisco's Barbary Coast dance halls in the early 20th century.

In these dance halls, men who were outcast in mainstream society — Filipino men, European immigrants, felons and men with disabilities among them — would go and dance with white women for a “dime-a-dance” worth of company.

The sociologist Paul G. Cressey, in his 1932 analysis of taxi dance halls and the men who frequented them titled “The Taxi-Dance Hall,” wrote of young Filipino bachelors: “Dapperly dressed little Filipinos … come together, sometimes even in squads of six or eight, and slip quietly into the entrance.”

The group of young Filipinos, Cressey lamented, had ulterior motives. (A chapter in his book is dedicated to the issue of “The Filipinos.”)

“Orientals, and especially Filipino young men,” he wrote, “prove to be such lucrative sources of income that many young women, under the spur of opportunism, lay aside whatever racial prejudices they may have and give themselves to a thorough and systematic exploitation of them.”

He explained this idea further in an interview with the Chronicle, in which he noted that young Filipinos were the most populous demographic foxtrotting and swinging with the white girls at California taxi dance halls.

“To … most of the taxi dancers, a Filipino is a ‘fish’ to be exploited, a victim much easier to extract money from than white men,” he told the paper. “The Filipino, on the other hand, thinks the American girl beautiful and fascinating, but certainly not modest and ladylike according to Filipino standards.”

In these terms, the relationship was transactional, if littered with racist notions of Filipino culture and desire. The white woman got paid, the Filipino man was able to access companionship, if temporary, by doing “dime jigs” with women in these so-called “dens of iniquity.”

(In 1931, less than a tenth of the Filipino population in America were women — which further motivated the desire to splurge lavishly and gallivant with women from other ethnic groups.)

Laws prohibited the coupling of non-white men and white women, but these laws were effectively brushed aside as taxi-dance halls became breeding grounds for what many white Americans deemed to be immoral conduct and miscegenation.

Some accounts recalled the taxi dances being a tad more lurid than a good ol' swing, with grinding and neck-biting between the taxi girls and their dance partners.

A 1929 article in the Stockton Record went so far as to declare that “the insistence of Filipinos that they be treated as equals by white girls has been the chief cause of friction between the races.”

The idea ran rampant, but Filipino men were cavorting with white women anyway beyond their dancing — especially at these dance halls.

Some naive dancers, Cressey wrote, even grew fond of their Filipino suitors, pointing to “his suave manners, dapper dressing, and politeness” as factors for their illicit courtship.

Anti-Filipino racism persisted differently than other forms of Asian xenophobia. Cressey, the sociologist, said that Filipinos assimilated to American culture too well.

Rather, he noted that “the young Filipino in this country is, from the point of view of some people, too readily Americanized,” right down to their fashion. It was a stark contrast from the “other Oriental groups,” he wrote, that did not accommodate to American culture quickly enough. (Here, he casually overlooks the effect that American imperialism, even culturally, had on the Philippines.)

As signs of an economic downturn began to emerge, the suits became just another thing for white men to resent.

‘Branded as a social menace’

A scandal in late 1929 set into motion a massive wave of anti-Filipino violence.

Perfecto Bandalan, a 22-year-old lettuce grower living in Salinas, was caught by Watsonville police sharing the same room in a boarding house as two white girls, 16-year-old Esther Chemick and her 11-year-old sister Bertha.

Bandalan and Chemick, a United Press article said, were set to be engaged — and spuriously claimed that the girl’s mother sold her off to Bandalan. (Other reports alleged that the Chemicks’ mother wanted Bertha, her youngest, to be raised by Esther and Bandalan.) He was sentenced to nine months in prison.

The incident, with the subtext being a Filipino preying on two young white girls, made waves throughout the state, and served as a vital flashpoint for white folks who deemed Filipinos a social ill.

A photo of Filipino laborers cutting asparagus on the Delta.

Courtesy of Holt-Atherton Special Collections, University of the Pacific Library

A resolution at a Monterey Chamber of Commerce meeting in January 1930 by D.W. Rohrbach, a Watsonville judge, declared the Filipinos “unwelcome inhabitants” — a message that reverberated through the local press.

Crucial to his incendiary, dehumanizing message was the contradiction of Filipinos withstanding slum-like living conditions but spending all their money on Macintosh suits and Florsheim shoes to perfect their appearance and woo women.

“For a wage that a white man cannot exist on, the Filipinos will take the job and, through the clannish, low standard mode of housing and feeding, practiced among them, will soon be well clothed,” the message from Rohrbach read, according to a 1930 article in the Pajaronian, “strutting about like a peacock and endeavoring to attract the eyes of the young American and Mexican girls.”

A week later, California GOP Rep. Richard J. Welch introduced legislation to curtail Filipino immigration. “This is the third Asiatic invasion of the Pacific coast,” he said in Congress, the Healdsburg Tribune reported. (In the same breath, he denied that he was prejudiced toward Filipinos.)

All this stoked the furies of Californians, fearful of Filipino men stealing their jobs and their girls.

Less than a week after Welch’s proclamation, the Monterey Bay Filipino Club, a taxi dance hall catering mostly to Filipinos, opened up in Watsonville. In protest, “trouble-seeking whites,” a King City Rustler article read, “cut the light wires to the dance hall and broke up the party.”

The turmoil between the manongs and the white men grew more dire. Nearly 500 white men and kids congregated at the club in opposition to it — and the white women employed at the club who resided in it.

The club’s white owner, Charles Paddon, and his brothers William and Edward, barricaded the entrances and shot at the mob with salt pellets.

A reporter with the King City Rustler said that non-Filipino entrants, including himself, were “challenged … to state their business” in order to prevent any altercations between Filipinos and whites.

Filipino men in Watsonville, regardless of whether they partook in the dancing, were hunted down and beaten en masse in one of the biggest riots in the town’s history, which lasted nearly a week. Some were thrown off bridges into the nearby river. Businesses that employed Filipinos were destroyed. Around 50 others were reportedly injured. Police were forced to hide men in City Council chambers.

The violence climaxed when Fermin Tobera, a 22-year-old laborer, was killed by gunfire while hiding from the rioters. His body was anointed and sent back home to the motherland.

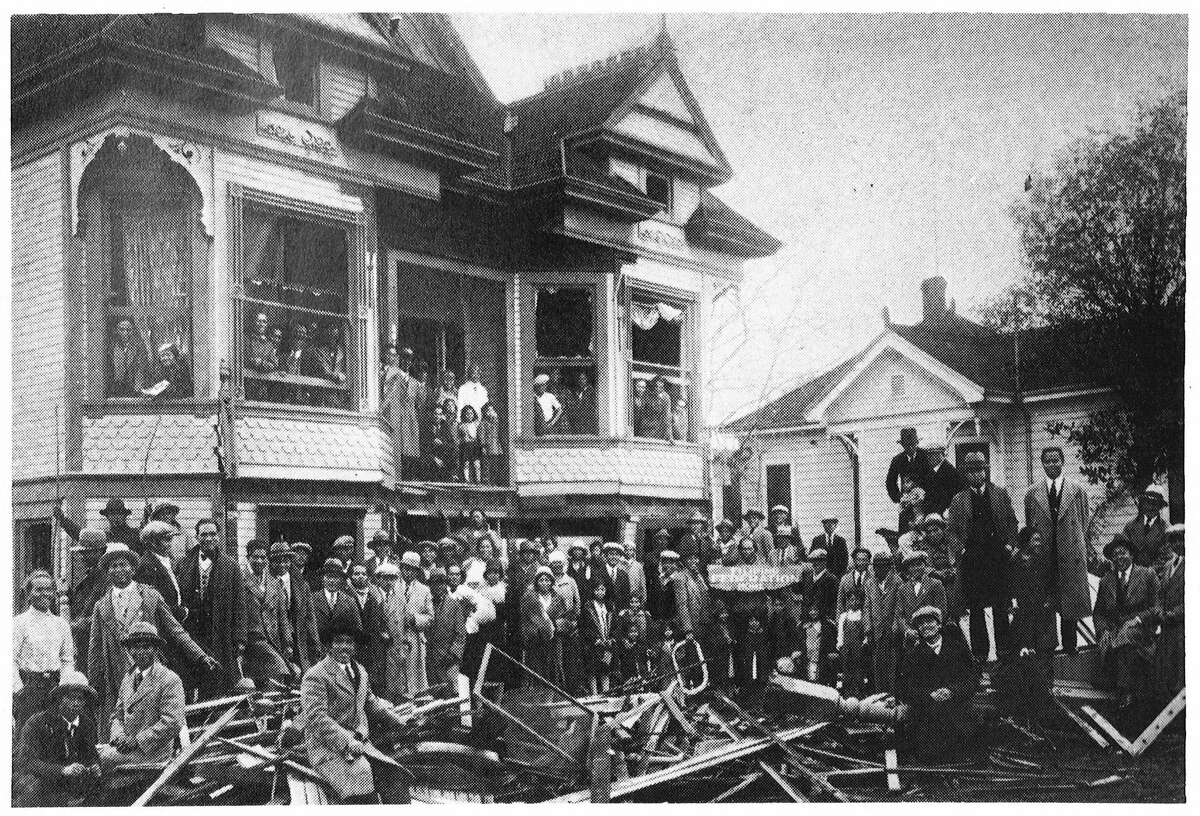

A photo published in a Healdsburg Tribune issue from 1930, showing the wreckage from the FFA headquarters.

Healdsburg Tribune/Archive

Only eight of the hundreds of white rioters were detained. Four were charged, but only one faced a short stint in jail.

Filipinos in the Bay Area were incensed. One man present at the Watsonville riots said, “We do not want to be branded as a social menace and the scum of the earth. Furthermore, we are under the American flag, and deserve some consideration.”

Other “race riots” throughout the Bay Area emerged in the wake of Watsonville, including in San Francisco, San Jose and Stockton.

By this point, a backlash of sorts to the taxi dance halls and their attendees emerged in the Filipino community. The most prominent group to do so was the Filipino Federation of America (FFA), headquartered in Stockton.

Also wearing their finest Macintosh suits in white, as if to align themselves to puritanical good graces, the members of the FFA decried their fellow countrymen’s moral indiscretions and sought acceptance from white Americans.

“He must keep from dancing, drinking alcoholic drink, gambling, smoking, pool halls, strikes, violence, resistance, and all things that are destructive to humanity,” read the group’s constitution.

The suits, rather than flaunting a degree of success and desirability, were deployed as a show of respectability. Roces wrote that their “motivation for this refashioning of the Filipino male was to prove that Filipinos were not a ‘social problem.’”

Their efforts were to no avail. Shortly after the Watsonville riots, the FFA headquarters were bombed, left in shambles. Its occupants were thrown out of windows. They were blamed for perpetrating the attack on their own building.

Members of the Filipino Federation of America stand in front of their clubhouse following the Stockton bombing in 1930.

Courtesy of Holt-Atherton Special Collections, University of the Pacific Library

The riots persisted well into the Great Depression. In 1934, a weekslong farmers’ strike in Salinas reached a fever pitch when Filipino farmworkers were shot at and their labor camp burned down, a response to increased hostility toward a Filipino labor union. The Healdsburg Tribune reported that it was seemingly in retaliation to a deputy and a highway patrolman being injured in the midst of the strike.

But shortly after, the threat of the Filipino was contained.

The Tydings-McDuffie Act, signed in 1935, eventually succeeded in curtailing Filipino migration to the U.S. for good, a crummy compromise that appeased the anti-Filipino movement and promised Philippine independence. In doing so, the law brought Filipino immigration to a screeching halt, admitting only 50 Filipino nationals a year to the country.

Macintosh suits also lost their luster in Hollywood come World War II. As the '30s studio system gave way to the Hays Code, so too did the excesses of the suits.

Glimmers of the Macintosh style lingered with the emergence of zoot suits, popularized by the jazz musician Cab Calloway and among Black, Filipino and Latino men of the era. It became the style that men of color wore in the World War II era, a sartorial protest over the rationing restrictions imposed during the time.

Taxi dance halls' popularity started to wane after the war, and started to largely shut down in the '50s and '60s just as Macintosh was clinging to its legacy of dressing Hollywood’s finest in those advertisements.

The Macintosh Studio shop at 222 Powell St. shut down in 1984, and its building now stands as Sam's Cable Car Lounge. But for Filipinos of a certain age, beyond its celebrity heritage, the memory of the suits lives on as an aspirational item and as a sometimes-painful reminder of their standing in American history.