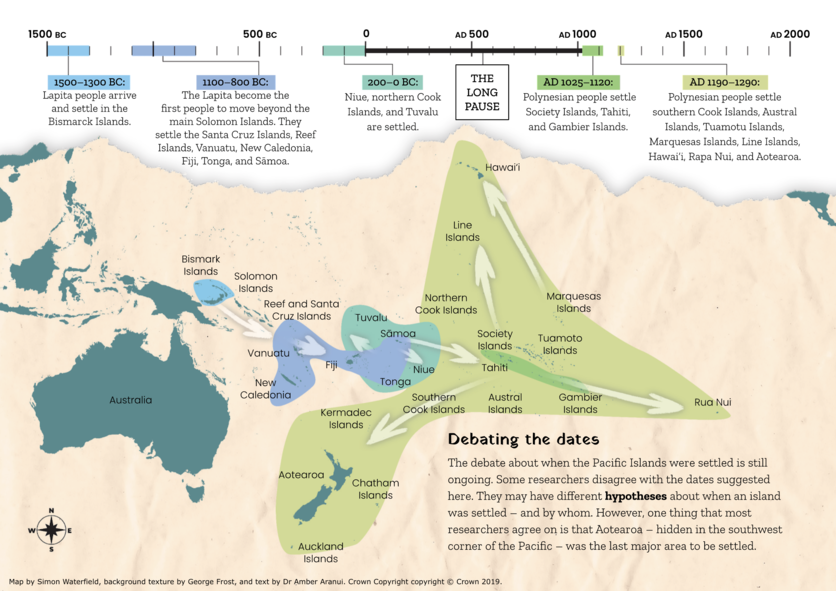

Known distribution of the Lapita culture

Reconstruction of the face of a Lapita woman. National Museum of Ethnology, Osaka. Reconstruction showed she had thick lips, wide nose, straight hair

The Lapita culture is the name given to a Neolithic Austronesian people and their material culture, who settled Island Melanesia via a seaborne migration at around 1600 to 500 BCE.[1] They are believed to have originated from the northern Philippines, either directly, via the Mariana Islands, or both.[2] They were notable for their distinctive geometric designs on dentate-stamped pottery, which closely resemble the pottery recovered from the Nagsabaran archaeological site in northern Luzon. The Lapita intermarried with the Papuan populations to various degrees, and are the direct ancestors of the Austronesian peoples of Polynesia, eastern Micronesia, and Island Melanesia.[3][4][5]

Etymology[edit]

The term 'Lapita' was coined by archaeologists after mishearing a word in the local Haveke language, xapeta'a, which means 'to dig a hole' or 'the place where one digs', during the 1952 excavation in New Caledonia.[6][7] The Lapita archaeological culture is named after the type site where it was first uncovered in the Foué peninsula on Grande Terre, the main island of New Caledonia. The excavation was carried out in 1952 by American archaeologists Edward W. Gifford and Richard Shulter Jr at 'Site 13'.[6] The settlement and pottery sherds were later dated to 800 BCE and proved significant in research on the early peopling of the Pacific Islands. More than 200 Lapita sites have since been uncovered,[8] ranging more than 4,000 km from coastal and island Melanesia to Fiji and Tonga with its most eastern limit so far in Samoa.

Artifact dating[edit]

'Classic' Lapita pottery was produced between 1,600 and 1,200 BCE on the Bismarck Archipelago.[4] Artifacts exhibiting Lapita designs and techniques from a period later than 1,200 BCE have been found in the Solomon Islands,[9] Vanuatu and New Caledonia.[4][10] Lapita pottery styles from around 1,000 BCE have been found in Fiji and Western Polynesia.[4]

In Western Polynesia, Lapita pottery became less decorative [3] and progressively simpler over time. It seems to have stopped being produced altogether in Samoa by about 2,800 years ago, and in Tonga by about 2,000 years ago.[4]

Material culture[edit]

Lapita pottery from Vanuatu, Museum in Port Vila.

Prehistoric pottery vessels, including some with Lapita designs, from the island of Taumako

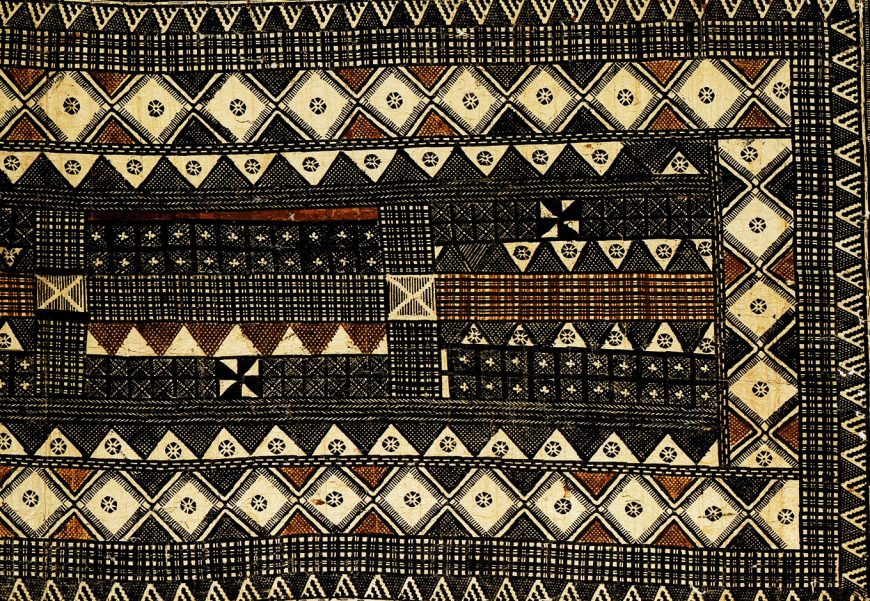

Pottery whose detailed decorative designs suggest Lapita influence was made from a variety of materials, depending on what was available, and their crafters used a variety of techniques, depending on the tools they had.[11] But, typically, the pottery consisted of low-fired earthenware, tempered with shells or sand, and decorated using a toothed (“dentate”) stamp.[3] It has been theorized[12] that these decorations may have been transferred from less hardy material, such as bark cloth (“tapa”) or mats, or from tattoos, onto the pottery – or transferred from the pottery onto those materials. Other important parts of the Lapita repertoire were: undecorated ("plain-ware") pottery, including beakers, cooking pots, and bowls; shell artifacts; ground-stone adzes; and flaked-stone tools made of obsidian, chert, or other available kinds of rock.[13][3]

Economy[edit]

The Lapita kept pigs, dogs, and chickens. Horticulture was based on root crops and tree crops, most importantly taro, yam, coconuts, bananas, and varieties of breadfruit. These foods were likely supplemented by fishing and mollusc gathering. Long-distance trade was practiced; items traded included obsidian,[14] adzes, adze source-rock, and shells.[3]

Burial customs[edit]

In 2003, at the Teouma archeological excavation site on Efate Island in Vanuatu, a large cemetery was discovered, including 25 graves containing burial jars and a total of 36 human skeletons. All the skeletons were headless: At some point after the bodies had originally been buried, the skulls had been removed and replaced with rings made from cone shells, and the heads had been reburied. One grave contained the skeleton of an elderly man with three skulls sitting on his chest. Another grave contained a burial jar with four birds looking into the jar. Carbon dating of the shells placed this cemetery as having been in use around 1000 BCE.[15]

Settlements[edit]

Lapita culture villages on islands in the area of Remote Oceania tended not to be located inland, but instead on the beach, or on small offshore islets. These locations may have been chosen because inland areas – for example in New Guinea – were already settled by other peoples. Or they may have been chosen in order to avoid areas inhabited by mosquitoes carrying malaria microbes, against which Lapita people likely had no immune defence. Some of their houses were built on stilts over large lagoons. In New Britain, however, there were inland settlements; they were located near obsidian sources. And on the islands at the eastern end of the archipelago, all settlements were located inland rather than on the beaches – sometimes fairly far inland.

Distribution[edit]

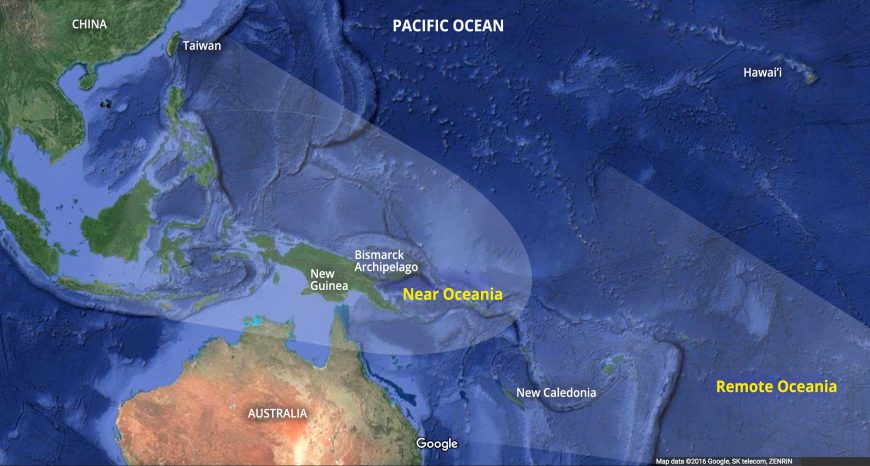

Lapita pottery has been found in Near Oceania as well as Remote Oceania, as far west as the Bismarck Archipelago, as far east as Samoa, and as far south as New Caledonia.[3][4] Excavation at a site in the village of Mulifanua in Samoa uncovered two adzes that strongly indicate Lapita influence. Carbon dating of material found with the adzes suggests there was a Lapita settlement at this site in roughly 1000 BCE.[16] Radio carbon dating of sites in New Caledonia suggest there were Lapita settlements there as early as 1,110 ago.[17] The dates and locations of more northerly Lapita-influenced settlements are still largely up for debate.[3]

Language[edit]

Linguists and other researchers theorize that the people of the Lapita cultural complex spoke a proto-Oceanic language, which is a branch of the Austronesian language family widely distributed in Southeast Asia today.[18][19] However, the particular language or languages spoken by the Lapita is unknown. The languages spoken in the region today derive from a number of different ancient languages, and material culture uncovered by archaeology does not generally provide clues to the language spoken by the makers of the artifacts.[18]

The Lapita complex is part of the eastern migration branch of the Austronesian expansion, which started from Taiwan[20] between about 5,000 and 6,000 years ago. Some of the emigrants reached Melanesia. There are different theories about the route they took to get there. They may have gone through the Marianas Islands, or through the Philippines, or both.[2] The strongest support for the theory that the original people of the Lapita culture were Austronesian is linguistic evidence showing very considerable lexical continuity between Proto-Malayo-Polynesian (presumably spoken in the Philippines) and Proto-Oceanic (presumably spoken by the Lapita people). In addition, the patterns of linguistic continuity correspond to patterns of similarity in material culture.[15][21]

In 2011, Peter Bellwood proposed that the initial movement of Malayo-Polynesian speakers into Oceania was from the northern Philippines eastward into the Mariana Islands, then southward into the Bismarcks. An older proposal was that Lapita settlers first arrived in Melanesia via eastern Indonesia. Bellwood’s proposal included the possibility that both migration patterns happened, with different migrants taking different routes.[23] Bellwood’s proposal is supported by the pottery evidence: Lapita pottery is more similar to pottery recovered from the Philippines (at the Nagsabaran archaeological site on Luzon Island) than it is to pottery discovered anywhere else. Other evidence suggests that the Luzon area may have been the original homeland of the stamped pottery tradition that is carried forward in Lapita culture.[24]

Archaeological evidence also broadly supports the theory that the people of the Lapita culture are of Austronesian origin. On the Bismarck Archipelago, around 3,500 years ago, the Lapita complex appears suddenly, as a fully-developed archaeological horizon with associated highly developed technological assemblages. No evidence has been found on the archipelago of settlements in earlier developmental stages. This suggests that the Lapita culture was brought in by a migrating population, and did not – as had been proposed in the 1980s and 1990s by scholars like Jim Allen and J. Peter White – evolve locally.

There is evidence that western Melanesia was continuously occupied by indigenous Papuans beginning between 30,000 and 40,000 years ago. That evidence includes recovered artifacts. But those remnants of the older material culture are far less diverse than the relics dating from after the Lapita horizon. The older material culture appears to have contributed only a few elements to the later Lapita material culture: some crops and some tools.[21][25]

The vast majority of the Lapita material-culture elements are clearly Southeast Asian in origin. These include pottery, crops, paddy field agriculture, domesticated animals (chickens, dogs, and pigs), rectangular stilt houses, tattoo chisels, quadrangular adzes, polished stone chisels, outrigger boat technology, trolling hooks, and various other stone artifacts.[21][25][23] Lapita pottery offers the strongest evidence of an Austronesian origin. It has very distinctive elements, like the use of the red slips, tiny punch marks, dentate stamps, circle stamps, and a cross-in-circle motif. Similar pottery has been found in Taiwan, the Batanes and Luzon islands of the Philippines, and the Marianas.[24]

The orthodox view, advocated by Roger Green and Peter Bellwood, and accepted by most specialists today, is the so-called "Triple-I model" (short for “intrusion, innovation, and integration"). This model posits that the Early Lapita culture arose as the result of a three-part process: “intrusion” of the Austronesian peoples of the islands of Southeast Asia (and their language, materials, and ideas) into Near Oceania; “innovation” by the Lapita people, once they reached in Melanesia, in the form of new technologies; and “integration” of the Lapita peoples into the pre-existing (non-Austronesian) populations.[26][24]

In 2016, DNA analysis of four Lapita skeletons found in ancient cemeteries on the islands of Vanuatu and Tonga showed that the Lapita people had descended from inhabitants of Taiwan and of the northern Philippines.[27] This evidence of the Lapita peoples’ migration route was corroborated in 2020 by a study that did a complete mtDNA and genome-wide SNP comparison of the remains of early settlers of the Mariana Islands with the remains of early Lapita individuals from Vanuatu and Tonga. The results suggest that both groups had descended from the same ancient Austronesian source population in the Philippines. The complete absence of "Papuan" admixture in these remains suggest that the voyages of the migrants bypassed eastern Indonesia and the rest of New Guinea. The study authors noted that their results also support the possibility that early Lapita Austronesians were direct descendants of the early colonists of the Marianas (who preceded them by about 150 years); this idea is also consistent with the pottery evidence.[28]

Recent DNA studies show that the Lapita people and modern Polynesians have a common ancestry with the Atayal people of Taiwan and the Kankanaey people of the northern Philippines.[29]

Lapita in Polynesia[edit]

As the archaeological record improved in the 1980s and 1990s, the Lapita people were found to be the original settlers in parts of Melanesia and Western Polynesia.[30] Many scientists believe Lapita pottery in Melanesia to be proof that Polynesian ancestors passed through this area on their way into the central Pacific. The earliest archaeological site in Polynesia is in Tonga.[31]

Other early Lapita discovery sites dating back to 900 BCE are also found in Tonga and contain the typical pottery and other archaeological "kit" of Lapita sites in Fiji and eastern Melanesia of about that time and immediately before.[32][33]

Anita Smith compares the Polynesian Lapita period with the later Polynesian Plainware ceramic period in Polynesia:

"There do not appear to be new or different kinds of evidence associated with plain-ware ceramics (& lapita), only the disappearance of a minor component of material culture and faunal assemblages is apparent. There is continuity in most aspects of the archaeological record that appears to mimic post Lapita sequences of Fiji and island Melanesia (Mangaasi and Naviti pottery).”[33]

Plainware pottery is found on many Western Polynesian islands and marks a transitional period between when only Lapita pottery was found and a later period before the settlement of Eastern Polynesia when the Western Polynesians of the time had given up pottery production altogether. Archaeological evidence indicates that plainware pottery ceases abruptly in Samoa around 1 CE.

According to Smith:

"Ceramics were not manufactured by Polynesian societies at any time in East Polynesian prehistory".[33]

Matthew Spriggs stated: "The possibility of cultural continuity between Lapita Potters and Melanesians has not been given the consideration it deserves. In most sites there was an overlap of styles with no stratigraphic separation discernible. Continuity is found in pottery temper, importation of obsidian and in non-ceramic artefacts".[34]

See also[edit]