More information about the Luzon Jars.

High-priced pots

Just how much they valued the sacred jars can be seen in the amount they were willing to spend on these items, or by their refusal to part with them at any price.

The sacred jar owned by the Datu of Tamparuli in Borneo, was originally sold to a merchant by a Malau chief for two tons of brass cannons, the equivalent in the mid-1800s to 230 pounds sterling. The merchant sold it to the datu for the equivalent in rice of 700 pounds sterling.

When the Sultan of Brunei was offered the equivalent of $100,000 to part with his sacred jar, he said that no offer would be sufficient. Water from the jar was believed to have special magical properties and visiting farmers from as far as the Bisayas in the Philippines were said to have come to obtain a little magic water for their fields.

For the Japanese, the Luzon jar was important because it was the only vessel capable of storing high-quality tea to their liking. From various reports, the jars also appeared to have been viewed as having medicinal and spiritual properties.

The most sensational report of one of these containers comes from Carletti, who reported that the best of the tea-canisters were valued at up to 30,000 pounds sterling, or about US $4 million in 2006 dollars. And these jars were actually used to store tea or tea leaf!

Europeans were astonished at the high amounts paid for these jars, all of which were old, the older the better, and of uncomely appearance. A similar situation was found in Borneo.

Rusun ("Luzon") Sukezaemon's story is well-known in Japan. The Sakai merchant brought back 50 Luzon jars and sold them to agents of the Shogun. He became fabulously rich and built a mansion that put the local castles to shame.

According to Antonio de Morga, the most valued jars sought by the Japanese were dark brown in color. Baron Alexander von Siebold confirms this and gives a more detailed description:

The best of them which I have seen were far from beautiful, simply being old, weather -worn, black or dark-brown jars, with pretty broad necks, for storing the tea in...Similar old vessels are preserved amongst the treasures of the Mikado, and the Tycoon, as well as in some of the temples, with all the care due to the most costly jewels, together with documents relating to their history.

Frank Brinkley, in the early 20th century, describes the tea ritual performed by the On-mono-chashi, the Shoguns' tea deputies who wore samurai uniforms, and fetched the "exceedingly homely jars of Luzon pottery to which the Japanese tea-clubs attached extraordinary value."

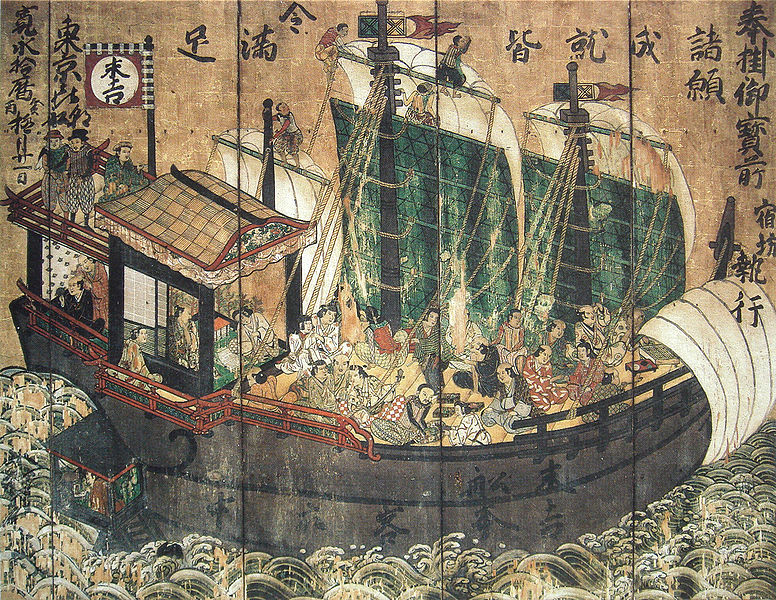

Every year the Shogun's tea-jars were carried to Uji to be filled. This proceeding was attended with extraordinary ceremonial [sic]. There were nine choice jars in the Shogun's palace, all genuine specimens of Luzon pottery, and three of these were sent each year in turn, two to be filled by the two "deputy families;" the third by the remaining nine families of On-mono-chashi. The jars were carried in solemn procession headed by a master of the tea-cult (cha-no-yu) and a "priest of tea," and accompanied by a large party of guards and attendants. In each fief through which the procession passed it received an ostentatious welcome and was sumptuously feasted. On arrival at Uji the jar, which always left Yedo fifty days before midsummer, stood for a week in a specially prepared store until every vestige of moisture had been expelled, and then, having been filled, were carried to Kyoto and there deposited for a space of one hundred days.

It's quite apparent that these are not celadons as postulated by some. The Japanese were aware of the celadons in Luzon (Rusun no seiji) which they described as shuko seiji "pearl-gray celadon," but these were different than the most valued dark-colored tea-canisters.

Europeans of the 16th century praised and imported both porcelain and celadon from the East. The communion cup of Archbiship Warham, the Lord Chancellor of England from 1504 to 1532, for example, was an imported celadon.

However, European observers of that time and afterward universally disparaged the Luzon tea-canisters. They also refer to these vessels repeatedly as earthenware.

According to the Tokiko, tea leaf kept its quality in these canisters if it touched the bottom or sides of the jar. Thus, it appears that contact with the clay was required to preserve the tea.

In Borneo and the Philippines, the sacred jars are often dated back to the first creation, and the clay is said to come from the gods.

The common division of sacred jars in Borneo mentioned by observers rates the Gusi type, a medium-sized, olive-green-colored jar with "medicinal properties" as having the highest value, followed by the Naga or "dragon jar." The latter is larger than the Gusi and is decorated with Chinese dragon figures. Last comes the Russa jar which is decorated with a representation of a type of deer.

Jars called "Gusi" also appear in the Philippines and Malaysia. They are mostly small to medium-sized but can be of many different colors. Some are stoneware, but most appear as glazed earthenware containers. A type of dark-brown Gusi known as Bergiau was found among the Sea Dayaks and was of higher value than the greenish Gusi.

Although of obvious Chinese influence, geochemical testing and other evidence suggests that dragon jars or Naga were made throughout the Southeast Asian region.

The dragon jars in the Philippines have a unique geochemical signature, but evidence shows that they also imported many dragon jars from elsewhere including the Martabans of Myanmar (Burma).

The sacred origin of the jars is a widespread motif in the region. In Ceram, pottery is one of the divine excretions of the earth goddess Hainuwele.

In Borneo, the sacred jars are made from the clay left over from the creation of the Sun and Moon by Mahatala, or his subject spirits. The Ngaju considered the vessels gifts of the gods, the fruit of the Tree of Life.

Among the Tinguian of the Philippines, the jars are also gifts, from the Sun or Sky-god Kabunian.

Quote

Quote